an introduction to the Salem witch trials by a literal banana

Why do humans and bananas alike get seduced into obsession with the events in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692? It’s not the mystery of why twenty people were executed, and hundreds imprisoned, for a supernatural crime. It’s not the mystery of why everyone suddenly got tired of hanging witches in a matter of months. It’s not the mystery of why it was the last witch trial of its scale in the Western world. And it’s not the play written by a communist that everyone had to read in high school, which functions as a curiosity repellant.

In fact, as you will quickly learn if you begin to study Salem, the fascination lies in an ancient dispute between two men of Boston, one of whom had no involvement in the Salem witch trials at all. The first, the politically connected minister Cotton Mather, wrote the first history of the Salem witch trials in the immediate aftermath of the event, Wonders of the Invisible World, attempting to whitewash the affair and justify the executions. The second, the humble but successful weaver and merchant Robert Calef, did not much like this, and wrote the second history of the trials a few years later, More Wonders of the Invisible World. They came to very different conclusions.

Ever since, it has been a tradition for Salemheads to take a side in this dispute. The side you choose is important, because it informs all the decisions you will arrive at about the import of each piece of evidence. Your judgments about every question arising from the tragedy will have curious relevance to the matter of which man you back in this antique beef.

Say you take Cotton Mather’s part, for example. Mather argued that demonic forces were assaulting Massachusetts, beginning years before the Salem tragedy (especially in his 1689 book Memorable Providences). In his history of the Salem witch trials (and for the rest of his life) he attempted to vindicate the judges and accusers, and insisted that the condemned witches were, in fact, guilty. In this case, you might find it convenient to argue that the witch belief was ubiquitous—or even, as some scholars have gone so far as to argue, that witchcraft was actually real, and that the executed witches really deserved to die. You might be tempted to ignore or reinterpret evidence that makes Cotton Mather look like a fool.

Robert Calef, on the other hand, argued that the supposed witchcraft was never real, that the condemned were innocent, that the accusers were frauds, and that a great injustice took place. If you take his part, you might emphasize the doubters who dared to express their doubts at the time and long before, and acknowledge that witchcraft isn’t real. You are free to argue that the tragedy at Salem was the result of solely human agency, including the agency of moral entrepreneurs. And you will delight in evidence that makes Cotton Mather look like a fool, especially if he wrote it himself.

This illustrates the problem with trying to tell just a little piece of the history of the Salem witch trials: everything is connected to everything else. Nevertheless, my hope with this introduction is to tell a small but critically important part of the story, and to gesture at how it connects with all the rest. For me, as a Calef partisan, that small piece is A Brand Pluck’d Out of the Burning, Cotton Mather’s narrative of Mercy Short. It was written in 1693, circulated among his friends, lost to history, and rediscovered hidden away in some dusty desk almost two centuries later. It was first published in complete form by George Lincoln Burr in his 1914 compendium of Salem sources, Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases, 1648-1706, and you can read it for free (it starts on page 255).

I choose this text not just because it is very interesting and funny and makes Cotton Mather look like a fool, but because it highlights one of the most important and frequently neglected aspects of the events: the fraud, deceit, magic tricks, and pranks conducted by the accusers. We get a more detailed picture here than in any other case study.

If you’ve heard one thing about the witch trials, you’ve probably heard of the theory that the whole tragedy was caused by ergot poisoning from moldy grain. This is part of a genre of medical excuses offered for the accusers, ranging from ergot, Lyme disease, or encephalitis on the one hand, to more psychological but still medical diagnoses like “hysteria” (or the more modern “conversion disorder”) on the other. The latter is a way for fans of the spooky and mysterious to preserve their prescientific world model while pretending to be scientific. The main point of my argument is that there was in fact nothing spooky or mysterious about the events in Salem. Neither demonic nor psychological explanations are indicated.

For many behaviors of the accusers, it may be difficult to convincingly distinguish innocent psychological causes (in the vein of “hysteria”) from conscious fraud. For other behaviors, however, conscious fraud is the only conclusion—specifically, behaviors requiring premeditation, practice, intentional deception, and/or collusion with confederates. Fainting and convulsing might be argued to be symptoms of hysteria (even the peculiar pattern exhibited by the accusers, which would conclusively rule out non-psychological medical causes), but performing magic tricks or elaborate group pranks must be ruled conscious fraud. That is why the narrative of Mercy Short is so important.

The Sport of Mercy Short

When Mercy Short was about fourteen years old, her parents were killed by the French and Indians, and she was taken captive, along with her brothers and sisters. They were taken to Canada, and about eight months later these hostages were “redeemed” and brought to Boston. Even if you find her subsequent behavior to be very naughty, you must admit that she had been through a great deal of trauma. Her behavior was also, with exceptions, extremely funny, and to my knowledge she did not actually get anyone judicially murdered, unlike the accusers at Salem.

In the summer of 1692, when Mercy Short was probably sixteen and the Salem witch trials were in full swing, she first displayed the by-then-stereotypical symptoms of being bewitched. Mercy, who was working as a servant in Boston, was sent by her mistress on an errand to the Boston jail, where the accused witches of Salem were being held. There, she supposedly encountered Sarah Good (Cotton Mather calls her “the Hag”) who, along with her four-year-old daughter, was imprisoned as a suspected witch. Goodwife Good asked Mercy for some tobacco, and Mercy threw a “handful of shavings” at her in answer, saying “that’s tobacco good enough for you!” Goodwife Good bestowed some choice words upon her, and that’s when Mercy Short first presented with the “fits” of the bewitched. History does not tell if she met anyone else on her errand to the prison, though we will see that she had an extensive social network.

Mercy spent a few weeks having fits and “fasting” for up to twelve days (the mystery of her fasts will soon be explained), but she got tired of it and went back to normal until November of 1692, about a month after the witch trials fell apart and the Court of Oyer and Terminer (the special witch court) was dissolved. Around November 22 she began to have fits again, and fasted for nine days, but again got tired of it, at least for three days.

At the end of those three days, though, around December 4th, she attended Cotton Mather’s church and made a terrible scene, pretending to see spirits around her and again having fits. The men of the church carried her, probably kicking and screaming, to the house of the nearest neighbor who would take her in, and there she stayed for several more weeks. She repeated the cycle at least one more time, getting better for a while and then having another tantrum in church, until her final deliverance on March 16, 1693. (For those counting, that is four cycles of possession over about ten months.)

Now we will see all the tricks that she got up to during her episodes of spirit possession, which Cotton Mather admirably records in enough detail for us to interpret what was really going on. His fans are correct in finding him to be an excellent and detailed observer, at least for facts that he thought would improve his case.

Cotton Mather notes that up to “half an hundred” people would be present to watch Mercy Short perform.

Sleight of Hand

Cotton Mather reports that Mercy Short could make solid objects disappear, and in some cases, reappear. For example, she picked his pocket and relieved him of a gold ring, then notified him that the spirits had taken it. He was amazed, and even more amazed when she told him where to find it—and indeed, there it was!

Shee fell a Laughing at One in the Room [note: this is how Cotton Mather talks about himself], and asked him, Whether hee had not a Gold Ring about him? Hee knew hee had, and look’d for it in the pocket where hee knew it was, but it was missing; and Shee, laughing, told him, That a Spectre had newly taken it out; but, said shee, “Look in such a Place and you shall find it.” Accordingly, hee Look’d and Found. Shee added, “They said, that if hee putt it on, They would have it off his Finger again before hee gott home.” Hee, to spite Them, Try’d; but tho’ hee diverse times between That and Home, thought his Finger taken with an odd Numbness, yett hee kept it on.

One of the explanations for the long fasts that so amazed Cotton Mather is simply that she did in fact eat and drink the whole time, which Cotton Mather admits, although he minimizes the amount: “One Raw Pear shee ate, and now and then an Apple, and some Hard Cider shee drank, things that would rather sett an Edge upon the Severity of her Fast: Sometimes also a Chestnut might go down into her Craving Stomach and sometimes a little Cold Water.”

But the more interesting explanation is revealed by Cotton Mather as another miracle: when she was offered food—biscuits or apples, perhaps—the “spirits” would snatch the treats out of her hand (that is, she would make them “disappear” into her sleeve by sleight of hand). Then she would complain that the spirits were eating them right in front of her, which of course no one else could see. To Cotton Mather’s credulous eyes, the food had disappeared and been eaten by specters. In reality, presumably she just saved it for later when she could eat without being observed.

The Impudence of the Troublesome Spectres was now somewhat more Daring and Broad-faced than formerly. It grew common with them to snatch from her such Apples and Biskets, as were given her to Try whether shee could eat them; so that no more could ever bee seen of them. And Mercy Short affirm’d, That shee saw the Spectres (tho’ wee could not,) eating them in the Room, what wee perceived they had stolen from her.

(Yet another explanation for the fasts is that she had confederates who could be relied on to bring her whatever she required in secret, as we shall see in the next section.)

Although a less impressive trick, Mercy Short also engaged in the practice of sticking pins into herself and saying that the specters had done it. This was a relatively common practice of the bewitched, both at Salem and across the ocean in England and Scotland. Sometimes she would prick herself and display the marks; other times she would leave the pins in for spectators to see. Sometimes she would sneak pins into her mouth and pretend that the spirits were forcing her to swallow them, so that the people hanging around her bedside (such as Cotton Mather) would have to pry her mouth open to remove them. Amazingly, they always succeeded in doing so before she could be forced by the specters to swallow them:

Besides the Thousands of cruel pinches given her by those Barbarous Visitants, they stuck innumerable pins into her. Many of those pins They did themselves pluck out again; and yett They left the Bloody Marks of them, which would bee as tis the strange Property of most Witch-wounds to bee, cured, perhaps in less than a Minute. But some of the Pins They left in her, and those wee took out, with Wonderment. Yea, sometimes They would force Pins into her Mouth, for her to swallow them; and tho’ Shee strove all shee was able to keep them out, yett They were too hard for her. Only before they were gott into her Throat, the Standers-by would by some Dexterity gett hold of them, and fetch them away.

Another genre of trick that amazed Cotton Mather was one involving books. For example, in her “trance,” Mercy Short would pick up a Bible, and without seeming to even look at it, would turn a few pages and fold down a leaf. It would just happen to be a verse with direct relevance to her current situation!

In her Trances, a Bible Happening to ly on her Bed, shee has taken it up, and without ever casting her Eye upon it, shee has Turned over many Leaves, at last folding down a Leaf to a Text, I holding up the Text unto the Spectres; but of all the Texts in the Bible, which do you think it was? T’was That, in Rev. 12. 12, The Divel is come down unto you, having great Wrath, because hee knows hee hath but a short Time.

This is a relatively simple trick to pull off, but one that would require preparation (locating appropriate verses in secret and memorizing or marking in order to find them again without seeming to look at the pages). She was happy to repeat this trick over and over, to pick out Bible verses or Psalms for the assembled company to sing. In one case, she even added a spooky bit of information to the trick, saying that the spirits told her the verse she’d found was one Cotton Mather had never preached upon—and it was true!

…and tho’ shee saw not the Text herself, yett Folding down a Leaf unto it, shee held it up unto the Spectres, for Them to Read it; adding withal, That her Name was already in that Book of the Lamb, and therefore it should never come into Their cursed Book! To which They Reply’d, Shee had shown them a Scripture which one (they named) had never yett preached upon: and in That, they spoke True.

Another trick Mercy Short performed was to (pretend to) read from the magical Devil’s book which the specters presented to her over and over. (According to the witch believers, the Devil and his minions would try to convince bewitched people to sign their special book, or even just touch it, to certify a contract with the Devil, which is how they claimed people became witches.) At one point, Mercy spelled out loud a word which is “too hard” for her, “Quadragesima,” and that Cotton Mather imagined she couldn’t possibly know except by reading it from the evil book. And, like the Bible verses she chose without looking, they were curiously relevant! Quadragesima is the first Sunday of Lent, in the Catholic faith which Cotton Mather regarded as diabolical (as we shall see more of later), which is why the demons would be talking about it. I can’t tell when exactly Quadragesima occurred in 1693, but by mentioning the date, Cotton Mather implies that he, at least, believed it to be curiously near in time. (Puritans did not celebrate holidays like Easter or Christmas, but Cotton Mather had a library of Catholic books for hate-reading, as we shall see.)

It particularly surprised some in the Room, on the Eve of March 9, 1693, to overhear her, in the Book then opened unto her, spelling a Word that was too hard for her; but from the best Judgment that could bee made of the Letters that shee recited, it was Quadragesima.

If he wasn’t simply imagining diabolical patterns in gibberish, presumably Mercy Short had overheard this word, or got it from one of her confederates especially for the prank—at least one of whom had access to Mather’s own library. We turn now to the evidence for an army of confederates.

Collusion with Confederates

The most daring prank that Mercy Short pulled off is the matter of the cat in the cockloft. She imperiously informed Cotton Mather that she desired a visit from him together with the governor of Massachusetts, Sir William Phips—and they obliged! When these distinguished gentlemen visited her bedside, she told them that she overheard the specters saying that they had dropped their evil, magical book, the book they used to sign up witches to bind them to the Devil. They dropped it, she told them, in the garret (attic) of a cockloft (an enclosed crawlspace at the very top of an attic) of a “person of quality” in the neighborhood, and if the gentlemen were to hurry they could retrieve the cursed book! They were suspicious that such a book even existed, and did not, in fact, hurry. But a few days later, they got around to sending a servant to check the cockloft—who was greeted by a spooky black cat jumping out over him! A cat, furthermore, never known to be at that house!

After the servant got jump scared, Mercy sent for Cotton Mather, and was very annoyed that he and the governor took so long to look for the book. In that time, she told him, one of the specters turned himself into a cat, and was in the process of retrieving the book when the servant came upon him in the cockloft. She knew all about this even though, Cotton Mather assures us, none of her attendants had told her anything about the cat. In Cotton Mather’s interpretation, she could have only known about it from the specters.

A more realistic interpretation, of course, is that Mercy Short arranged with confederates to lock up a poor cat in said cockloft, hoping to jump scare Cotton Mather and the governor, but succeeding only in scaring a servant. Nevertheless, the trick worked well enough to be recorded as a diabolical miracle. It leads Cotton Mather to some deep metaphysical speculations:

Whether the Cat were what was pretended, I shall give no Opinion: tho’ I know the Assertion of some, That every Spirit is endued with an Innate Power by which it can attract suitable matter out of all Things for a Covering or Body, of a proportionable Form and Nature to itself: which Assertion, Well stated, Proved, and Applyed, would solve some of the hardest Phenomena that belong to the uncouth and horrid Shapes, wherein mischiefs are done by Witchcraft.

Another prank involves interfering with Cotton Mather’s books from afar. Mercy Short told Cotton Mather that the specters had a certain book that they used for their diabolical rites, and whenever they wanted to use it, they would steal it from Cotton Mather’s own library. (Apparently, the book named is an utterly normal Catholic devotional book that Cotton Mather kept for hate-reading, as mentioned above. It was Catholic, so of course the devils loved it—the Puritans absolutely despised Catholics.) Mercy described the book in detail and “saw” the specters fold a page down, and indeed, in his own home, Mather found his own copy with its page folded down by the pesky devils. Not only did she have confederates—she had a mole in Cotton Mather’s own house! (Perhaps it was another servant girl.) She and her confederate repeated the trick again, in the night, after Cotton Mather had carefully checked that no pages were folded:

But that which added unto the surprise was, That hee found a Leaf doubled down in the Book, which hee could not conceive how it should come: and when a Night or Two after, just as hee went unto his Rest, hee left this Book on his Table in his Study, carefully seeing that there should not bee one Leaf at all folded in it; yett the next morning hee found Three Leaves unaccountably Folded, and then Visiting Mercy, hee perceived the Spectres bragging, That tho’ shee had [said] shee would warrant them, that Gentleman would keep his Book out of their Hands, yett they had Last Night stole the Book again unto one of their meetings, and folded sundry Leaves in it. [Again “hee” refers to Mather himself; this is just how hee is.]

She repeated the trick yet again, describing to him another Catholic book in his library that the specters liked to borrow. This time the specters told her they’ve returned it with the back side outwards, and when Cotton Mather checked, what the spirits told her was true! Cotton Mather takes this as evidence that Catholicism was even more diabolical than he’d supposed.

Mercy Short had sources that would tell her gossip, especially about herself, and Mather attributed this to diabolical messengers rather than confederates:

T’was an ordinary thing for the Divel to persecute her with Stories of what this and that Body in the Town spoke against her. The Unjust and Absurd Reflections cast upon her by Rash People in the coffee-houses or elsewhere, Wee discerned that the Divel Reported such Passages unto her in her Fitts, to discourage her.

There are many references in Cotton Mather’s writings to this hated coffee house and its “coffee-house wits,” hinting at the presence of a group of skeptics whose existence vexed him—two of whom may have been Robert Calef and Thomas Brattle (see the first section of the reading list).

Mercy performed long monologues while pretending to address the invisible specters, seeming, in Cotton Mather’s rendition, quite organized in her speech, and not like a rambling “distracted” person. She predicted a fire, and there was a fire; this may simply be coincidence, or a hint that her confederates were up to much worse mischief than we have seen so far. This is a piece of her monologue, with Cotton Mather’s note in parentheses:

Well if You do Burn mee, I had better Burn for an Hour or Two here then in Hell forever.—What? Will you Burn all Boston and shall I bee Burnt in that Fire?—No, tis not in Your Power. I hope God won’t lett you do that. (Memorandum, The Night after these Words were spoken, the Town had like to have been burn’t; but God wonderfully prevented it.)

Mercy reported that the specters were planning to have a Christmas dance in her room, which was doubly shocking, because neither Christmas nor dancing was halal according to the Puritans. And Mather reports that on “the twenty-fifth of December,” which is as close as he will come to mentioning the name of the forbidden holiday, the attendants in Mercy Short’s room did hear (and feel!) a dance. She would not have been able to perform this feat herself, and the description implies more than one hidden confederate to make the required noise:

On the twenty-fifth of December it was, that Mercy said, They were going to have a Dance; and immediately those that were attending her, most plainly Heard and Felt a Dance, as of Barefooted People, upon the Floor; whereof they are willing to make oath before any Lawful Authority.

It’s a common occurrence for Cotton Mather to threaten to provide witness statements on various incredible points, and on one point he actually followed through, as we will see in the next section.

The specters scratched on the bed and on the wall:

At other times there would be heard, it may bee, by more than seven Witnesses at a time, the Scratches of the Spectres on the Bed and on the Wall.

The demons scratched and pricked the visitors, which could either mean that the confederates were among the assembled company pretending to be pricked, or that the confederates were going around scratching and pricking innocent bystanders. The former interpretation is suggested by how fanciful some of the reports of spirit molestation are:

And whether it were from the Mistake or from the Malice of the Spectres, it was no Rare Thing for the Standers-by to have their Arms cruelly scratch’d, and Pins thrust into their Flesh, by these Fiends, while they were molesting of Mercy Short. Yea, several Persons did sometimes actually lay their Hands upon these Fiends; the Wretches were Palpable, while yett they were not Visible, and several of our People, tho’ they Saw nothing, yett Felt a Substance that seem’d like a Cat, or Dog, and tho’ they were not Fanciful, they Dy’d away at the Fright! This Thing was too Sensible and Repeated a Thing, to bee pure Imaginacion.

It should be noted that during this time, the church youth groups, “both sexes apart,” were meeting in Mercy Short’s chambers, providing a potential pool of confederates for her antics.

Often when the specters were moving around the room (according to Mercy Short), some visitors struck at the invisible specters with their swords. This touches on a widespread bit of witchcraft mythos, that a specter of a witch struck in invisible form would bear the wound in real life—a common motif both during the Salem panic and years before and after. But when the visitors who dared to strike at the specters eventually left and made their way home, the specters got their revenge by haunting and scaring them—and Mercy knew about it every time! Again, this could either be explained by her confederates pretending to have been haunted, or by her confederates actually following other visitors to scare them (possibly including Cotton Mather, as we have seen how he refers to himself in the third person in this and other texts he wrote on plausibly-deniable sock accounts, such as his biography of Sir William Phips). A somewhat darker story we will touch on presently hints at the latter.

It was particularly remarkable, That some who were very Busy in this method of treating the Spectres [striking them with swords], upon a presumption that they might bee corporally present, (tho’ covered with such a Cloud of Invisibilitie as Virgil, I remember, gave once unto his Eneas), were terribly scared with Apparitions in their journeyes home, whereof, tho’ they made no manner of Report, yett Mercy Short was presently after able to tell her Attendents; as having heard the Spectres brag unto her, and unto one another, how They had paid such and such for striking at them.

The cruelest prank that Mercy Short and her confederates committed is reported by Cotton Mather in his diary. Mather’s wife gave birth to a severely deformed baby who sadly did not live long. He suspected witchcraft in the matter, he says, because shortly before the birth, his wife was badly frightened by a specter on their porch. Mercy Short knew about it, and claimed the specters bragged about doing it. Which is to say, she was in on it.

I had great Reason to suspect a Witchcraft, in this preternatural Accident; because my Wife, a few weeks before her Deliverance, was affrighted with an horrible Spectre, in our Porch, which Fright caused her Bowels to turn within her; and the Spectres which, both before and after, tormented a young Woman in our Neighbourhood, brag’d of their giving my Wife that Fright, in hopes, they said, of doing Mischief unto her Infant at least, if not unto the Mother…

While we no longer believe that frights during pregnancy cause birth defects, scaring a pregnant woman severely enough to cause her physical distress was a foul and heartless thing for the Mercy Short gang to do, and puts a damper on our appreciation for their cleverness. Robert Calef mentions their “vicious courses” in later years.

While this has not been a complete list of the tricks and deceptions enacted by Mercy Short and her confederates, it is enough to get a strong sense of the proceedings, and of how these activities were interpreted by the minister Cotton Mather. I now turn to the relation of a few tricks pulled off by another Boston girl later that year, Margaret Rule.

As a reminder, Cotton Mather’s narrative of the Salem witch trials was called Wonders of the Invisible World, and his Mercy Short narrative was called A Brand Pluck’d Out of the Burning. His narrative of his next witchcraft case, that of Margaret Rule, would be creatively titled Another Brand Pluck’d Out of the Burning, Or, More Wonders of the Invisible World, a sort of double sequel. When Robert Calef would eventually publish his book as More Wonders of the Invisible World, this was not a title invented by Calef to mock Cotton Mather—it was Mather’s own choice, which makes it even funnier to me. It is available in Burr’s book beginning on page 308 (see the first section of the reading list, below).

The Fools of Margaret Rule

Cotton Mather’s careful observations reveal to us (though seemingly not to himself) the magic tricks, deceptions, and collusions of Mercy Short. Another aspect of the case comes through clearly to us, though apparently not to him—that the townspeople of Boston were getting tired of Mercy Short’s antics. Mather notices that citizens promised to show up to pray and fast for her, but tended to realize at the last minute that they had something more important to do, which he attributes to the work of the Devil:

It was also remarkable that when wee were intending a Day of Prayer, the Spectres would ussually advise her of our Intention, and brag that They would hinder the People from coming: According to which Brag of Theirs, t’was wonderful to see how many Pious Christians that were desirous to have been with us were hindered of their Desires, by unexpected occasions pressing in upon them.

At any rate, a new seventeen-year-old girl, Margaret Rule, entered the stage on September 10th, 1693, a few months after the conclusion of Mercy Short’s performance. Margaret Rule made her entrance in the same manner as Mercy: by having a fit in church. Like Mercy, she was carried home. She took to her bed to perform for onlookers, and especially for Cotton Mather, just as Mercy Short had.

Margaret Rule’s repertoire overlapped substantially with that of Mercy Short. She would pinch herself “black and blew” and stick herself with pins in the neck, back, and arms. She would fast for up to nine days, taking only spoonfuls of rum (at least in front of observers who were not her confederates). There were noises around the room that could only have come from specters. She knew gossip that could only have come from demons. It would get repetitive to list them all.

I will focus here on only two tricks pulled off by Margaret Rule. Both clearly required confederates, and it is possible that the same gang was involved, with different front-women performing the lead role, although there are suggestions that it may have been a rival gang.

The first trick is relayed in Cotton Mather’s diary (relevant passages reprinted in Burr’s book, and also available on page 173 of this edition). He had written up lecture notes for “discourses” that he intended to preach in church at Salem, and also to publish. Unfortunately, his lecture notes were stolen, and there could only be one culprit—Satan.

I had largely written three Discourses, which I designed both to preach at Salem, and hereafter to print. These Notes were before the Sabbath stolen from mee, with such Circumstances, that I am somewhat satisfied, The Spectres, or Agents in the invisible World, were the Robbers.

His suspicion was confirmed when Margaret Rule told him that the specters confessed to stealing his notes, but she consoled him that he’d get them back eventually:

As for my missing Notes, the possessed young Woman, of her own Accord, enquir’d whether I missed them not? Shee told mee, the Spectres brag’d in her hearing, that they had rob’t mee of them; shee added, Bee n’t concern’d; for they confess, they can’t keep them alwayes from you; you shall have them all brought you again.

As the final act of the trick, he found his notes again—completely preserved, but scattered around the streets of Lynn, Massachusetts, a few miles from Boston.

On the fifth of October following, every Leaf of my Notes again came into my Hands, tho’ they were in eighteen separate Quarters of Sheets. They were found drop’t here and there, about the Streets of Lyn; but how they came to bee so drop’t I cannot imagine; and I as much wonder at the Exactness of their Preservation.

Apparently, Margaret’s gang had returned to the tradition of lighthearted prank content. They stole Mather’s notes surreptitiously, let him know the devils had taken them, then returned them to him under circumstances guaranteed to amaze him. (However, her specters also bragged to her about stealing someone’s will, which was in fact stolen, and there’s no indication that it was returned.)

But Margaret Rule’s magnum opus was a prank so outlandish that scholars would debate it for hundreds of years. This magic trick was so controversial that it would be immortalized as a symbol of the feud between Cotton Mather and Robert Calef: she levitated to the ceiling in front of witnesses.

In Mather’s telling, from More Wonders of the Invisible World, the miracle is related in a single sentence in a long paragraph full of wonders, not particularly distinguished from any of the other tricks Margaret Rule was performing:

And once her Tormentors pulled her up to the Cieling [sic] of the Chamber, and held her there before a very Numerous Company of Spectators, who found it as much as they could all do to pull her down again.

There it may have stayed, in that lone sentence, if not for the Mather-Calef feud. For as Cotton Mather shifted his attention to the newest bewitched girl, Margaret Rule, Calef came to her chamber to see for himself, and took notes. Calef would end up publishing Mather’s narrative of the Margaret Rule case, Calef’s own notes, their correspondence, Mather’s narrative of the Salem witch trials, Calef’s own narrative of the Salem witch trials, and sundry other letters and arguments related to the scriptural and practical bases of witchcraft. Calef’s book More Wonders of the Invisible World would become the 1700 equivalent of what in modern drama would be an enormous Google document, although he scrupulously presented the materials of each side together, rather than just his own case and supporting evidence.

Cotton Mather was very upset to learn that someone disagreed with him. His letter to Calef in January of 1694 threatened to produce witness statements for a laundry list of claims (in lieu of argument), but in the end, he only produced witness statements for one claim: the levitation of Margaret Rule. “I suppose you expect I should believe it,” Calef replied drily. He published the witness statements with all the rest. Here they are:

I do Testifie that I have seen Margaret Rule in her Afflictions from the Invisible World, lifted up from her Bed, wholly by an Invisible force, a great way towards the top of the Room where she lay; in her being so lifted, she had no Assistance from any use of her own Arms or Hands, or any other part of her Body, not so much as her Heels touching her Bed, or resting on any support whatsoever. And I have seen her thus lifted, when not only a strong Person hath thrown his whole weight a cross her to pull her down; but several other Persons have endeavoured, with all their might, to hinder her from being so raised up, which I suppose that several others will testifie as well as my self, when call’d unto it.

Witness my Hand,

Samuel Aves.

We can also Testifie to the substance of what is above Written, and have several times seen Margaret Rule so lifted up from her Bed, as that she had no use of her own Lims to help her up, but it was the declared apprehension of us, as well as others that saw it, impossible for any hands, but some of the Invisible World to lift her.

Robert Earle.

Copia. John Wilkins.

Dan. Williams.

We whose Names are under-writted do testifie, That one Evening when we were in the Chamber where Margaret Rule then lay, in her late Affliction, we observed her to be, by an Invisible Force, lifted up from the Bed whereon she lay, so as to touch the Garret Floor, while yet neither her Feet, nor any other part of her Body rested either on the Bed, or any other support, but were also by the same force, lifted up from all that was under her, and all this for a considerable while, we judg’d it several Minutes; and it was as much as several of us could do, with all our strength to pull her down. All which happened when there was not only we two in the Chamber, but we suppose ten or a dozen more, whose Names we have forgotten,

Copia. Thomas Thornton.

William Hudson Testifies to the substance of Thorntons

Testimony, to which he also hath set his Hand.

Read over these brief descriptions and see if you can figure out how the trick was done. Of course, it is possible that the fabrication was Mather’s, and that he simply used his social position to pressure witnesses to lie for him. But I think there is a much simpler explanation.

Two of the most prominent Cotton Mather partisans are on record as not being able to figure it out. These two men, William Frederick Poole in 1869 and Chadwick Hansen in 1969, suggest that it’s entirely possible that Margaret Rule magically levitated.

William Frederick Poole was known to be such a shameless Cotton Mather dickrider that it was an academic joke. George Lincoln Burr opens his 1911 paper on New England witchcraft thus:

It is now more than twenty years since I reached the threshold of this theme. Happily it was to learn in time its perils. I was about to read before the American Historical Association a paper on “The Literature of Witchcraft” and my friend Mr. Justin Winsor naturally guessed that it must touch upon New England’s share. “Don’t be afraid,” he encouraged me, “to say just what you please. If Poole pitches into you, I’ll come to your support.”

While Burr assures us that he and Poole remained friends until the latter’s death, he acknowledges Poole’s role in the history of Salem scholarship. In a review of Charles Upham’s book on the history of Salem in 1869, Poole defends Mather from Upham’s perceived attacks (which were in that book mostly relegated to a footnote) thus:

Mr. Upham’s narrative proceeds in the same loose method: “So far was he successful in spreading the delusion, that he prevailed upon six men to testify that they had seen Margaret Rule lifted bodily from her bed and raised by an invisible power so as to touch the garret floor.” This, of course, seems to Mr. Upham very absurd ; but similar instances of elevation are recorded in modern times, and are believed in by those who accept the theory of spiritualism. A bed was lifted in this manner in the house of the Wesleys at Epworth. And Cotton Mather “prevailed upon six men” — Samuel Aves, Robert Earle, John Wilkins, Daniel Williams, Thomas Thornton, and William Hudson — to testify in three depositions to — what ? a fact? Testifying to a fact is a commonplace incident, and divests the statement of all its significance. The inference prepared for the reader is, that Mr. Mather prevailed upon six persons to testify to a falsehood— and all this without a particle of evidence to sustain the charge.

Thus Cotton Mather can count William Frederick Poole among his witnesses to the fact that Margaret Rule could have magically levitated to the ceiling. (I could almost take this as accepting my case that there was a rational but fraudulent explanation, if not for the mention that “a bed was lifted in this manner” at Epworth.) But although almost two hundred years removed from the feats of Mercy Short, Poole lived in a superstitious age in which many people who should have known better accepted Spiritualism and its deceptions as scientific fact.

William Frederick Poole was also the first to publish a summary of the Mercy Short narrative (A Brand Pluck’d Out of the Burning) after its discovery. Burr, about to drop the full Mercy Short narrative to the public in 1914, kindly refers to his old friend Poole’s 1881 summary as “careful,” but he is being more kind than honest. Imagine you have accepted Cotton Mather as your personal savior, and then someone digs out the Mercy Short narrative from behind a drawer in some ancient desk and you are forced to deal with it. Now that we have acquainted ourselves with how foolish Cotton Mather looks from the Mercy Short narrative, we can imagine ourselves in poor Poole’s position. I’m sure we can sympathize, emotionally if not intellectually, with the choice he made—that is, to simply leave out and ignore all the obvious magic tricks that Mercy Short performs. Chadwick Hansen, discussed below, would follow Poole’s lead and perform the same motivated elision.

Chadwick Hansen published his history of the Salem witch trials in 1969 (Witchcraft at Salem). Surely a mid-20th-century English professor wouldn’t believe that a girl could really levitate? But amazingly, Hansen is also willing to provide a witness statement for Cotton Mather. After reproducing all the witness statements I have also reproduced above, Poole says:

These statements might possibly describe an arc de cercle, a violently arched position of the body not uncommon in hysterical fits, which would raise the trunk of the body a considerable distance off the bed. Combined with the power of suggestion to affect bystanders’ senses, this might account for their belief that they had witnessed levitation.

So far so good—it’s a psychological theory, as Hansen leans hard on (mostly 19th century) psychology in his analysis, but at least it’s a theory. Unfortunately, he goes on:

Yet they were not simply bystanders; they were engaging in violent physical activity, trying to bring her body back to the bed. Such activity would, ordinarily, tend to break the power of suggestion. And levitation has been so frequently reported, from so many times and places (from the twentieth-century Indian fakir to the Medieval or Renaissance saint), that one cannot be at all sure there is a satisfactory explanation for it, particularly since so many witnesses insisted that no part of Margaret Rule’s body was touching the bed. In an arc de cercle the head and feet do, of course, touch.

Like Poole before him, Hansen leans toward the belief that Margaret Rule really levitated, for one “cannot be at all sure there is a satisfactory explanation.” (And if you imagined that scholars ceased to make this claim in the 21st century, you would be wrong.) However, now that you’ve had some time to think about it, I’ll reveal what I believe to be a satisfactory explanation for the whole business. Half of the solution can be found in textual clues, and the other half in an ancient item of children’s culture.

The Solution

Hopefully I have established by now that Cotton Mather was almost unfathomably credulous. He was fooled by very primitive magic tricks that do not seem to have convinced the “coffee-house wits.” He demands that others also believe, and frequently insults doubters as being heartless, atheists, or witch-advocates. It would not have taken a David Blaine to convince him of something that he desired with all his heart to believe. The trick could have been very clumsy, but as long as something happened that appeared vaguely like levitation, that would be enough for him to assert it, and to pressure his witnesses to go along with his assertion, even if they had their doubts.

The first piece of the puzzle is that Margaret Rule had accomplices. This can be surmised from many of her magic tricks that would have required confederates, such as the trick of stealing Cotton Mather’s papers and scattering them around Lynn, Massachusetts, for him to find. We even get a clue, from Calef’s account, to the name of one of her potential assistants: Margaret Perd. For example, Margaret Perd volunteered that she smelled brimstone in Margaret Rule’s room, and an unnamed other agreed, while Calef himself did not smell it. From all the available evidence, we can surmise that not only did Margaret Rule have confederates, they were frequently near her bedside.

The second piece is a certain detail from the event which is clearly indicated by the witness statements, which I again reproduce in relevant part:

And once her Tormentors pulled her up to the Cieling [sic] of the Chamber, and held her there before a very Numerous Company of Spectators, who found it as much as they could all do to pull her down again.

I have seen her thus lifted, when not only a strong Person hath thrown his whole weight a cross her to pull her down; but several other Persons have endeavoured, with all their might, to hinder her from being so raised up

it was as much as several of us could do, with all our strength to pull her down. All which happened when there was not only we two in the Chamber, but we suppose ten or a dozen more, whose Names we have forgotten

The critical detail is that in the crowded room, it appeared to the witnesses that many people were trying to pull Margaret Rule down from her levitation. Which is to say, many people were touching her, including, potentially, her confederates.

What if some of that number were not trying to pull her down, but were only pretending to pull her down, and were, in fact, lifting her up? We know from Calef’s account that when witnesses gushed about the strength required to move a bewitched person from their supposedly preternatural postures, they were exaggerating:

…the Attendants said that she was sometimes in a Fit that none could open her Joynts, and that there came an Old Iron-jaw’d Woman and try’d, but could not do it; they likewise said, that her Head could not be moved from the Pillow; I try’d to move her head, and found no more difficulty than another Bodies (and so did others) but was not willing to offend by lifting it up, one being reproved for endeavouring it, they saying angrily you will break her Neck…

So to the extent that some of the people touching Margaret Rule were trying to pull her down rather than trying to lift her, they probably weren’t trying very hard.

The third piece of the puzzle is a beautiful and ancient aspect of children’s culture, and particularly girl children’s culture. This is a “levitation” ritual that is sometimes known in our time as “Light as a Feather, Stiff as a Board.” It was first described in print by Samuel Pepys in his diary in 1665, though it is certainly much older. Given the mysterious ways by which children’s culture maintains itself, it would not be at all surprising if it were in New England in the late 17th century, even in such a notoriously strict culture. Pepys relates that his friend, Mr. Brisband, told him about a ritual Brisband had seen performed by four little girls. They repeat a magic spell, then

putting each one finger only to a boy that lay flat upon his back on the ground, as if he was dead; at the end of the words, they did with their four fingers raise this boy as high as they could reach

To Brisband’s surprise, they could “levitate” a fat cook, too!

The same basic ritual is described by the Opies in their book The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (1959), again with girl informants (page 309 of my 1987 edition), who participated in the ritual at school in Bath in the 1940s. And the Opies themselves report that they practiced the trick in their own childhoods, giving three variations. Elizabeth Tucker, writing in 2007 in the Children’s Folklore Review, finds that among her Introduction to Folklore students, all the women were familiar with the ritual, but several of the men were not, so the existence of this phenomenon may be news to some readers.

The Opies’ informant says, “It was more like real magic than anything else I have seen.” Indeed, that several people can lift another with only a finger or two each it is a surprising bit of physics that lends itself to the appearance of magic! It is very similar in principle to the phenomenon of crowd surfing, but conducted with more gravitas. If you know any children, you could ask them for more information or a demonstration, or watch one of the performances of the trick on YouTube.

That, I think, is the simplest explanation for how Margaret Rule “levitated”—she did it with a little help from her friends. We know from Calef’s account that her attendants frequently touched her, rubbing and stroking her to make her feel better. It’s easy to imagine a few of her accomplices gathered around tending to her, when suddenly one of them says, “oh look, she’s rising!” Then they all begin to lift her, while crying out for her to come back down, and pretending to pull her down.

I do offer a second possibility, though I think it is less likely. Cotton Mather describes many of the tricks performed by Mercy Short and Margaret Rule (as well as the Salem accusers) in his 1697 biography of Governor William Phips (whom we have previously met when Mercy Short invited him to be pranked). In this text (beginning on page 133, and also functioning as a sort of Greatest Hits of the deceptive magic tricks the girls pulled off) the closest description to the Margaret Rule levitation is this:

or if it were Preternatural to have one’s Hands ty’d close together with a Rope to be plainly seen, and then by unseen Hands presently pull’d up a great way from the Earth before a Croud of People; such Preternatural things were endured by them.

Thornton’s statement says that Margaret was lifted by invisible forces “so as to touch the Garret Floor,” a garret again being an attic, suggesting a space above her where confederates could have concealed themselves with a rope. If Cotton Mather is actually describing the Margaret Rule levitation event with this text, another solution is that she tied the bottom of a rope around herself (perhaps under her covers), and then her confederates in the attic pulled her up with the rope. A tiny bit of support for this theory is that Mather describes Margaret Rule as having been “pulled” up (although all the other witnesses say she was “lifted”), and also uses that verb in this text.

It’s likely, however, that Cotton Mather was describing a different event with this text, or conflating multiple events. While Mather’s use of the words “and then” suggests these events were part of a unified sequence, this may not be the case. Deodat Lawson’s narrative of the Salem witch trials includes a rope trick and a different kind of levitation trick, the latter not being witnessed by a crowd:

Some of the afflicted, as they were striving in their fits in open court, have (by invisible means) had their wrists bound fast together with a real cord, so as it could hardly be taken off without cutting. Some afflicted have been found with their arms tied, and hanged upon an hook, from whence others have been forced to take them down, that they might not expire in that posture.

In other words, the Salem girls hid cords in their sleeves or apron pockets, and secretly and deceptively tied their own hands when no one was looking (a trick that would likely require practice), then claimed that specters did it. Other times they tied each other up to be hanged by a hook like a stereotypical younger sibling or other victim of bullying, again blaming the specters. It’s very likely that Cotton Mather is referring to the Salem events described by Deodat Lawson, and not to Margaret Rule, when speaking of the “preternaturally” tied up girls, especially since neither he nor any other witness mentions a rope in the Margaret Rule case.

It would be odd for Mather to be so impressed with the stunt that he got witnesses to attest to it and then not mention it at all in this “Greatest Hits” selection a few years later, but perhaps he realized in the meantime that it invited especial disbelief. It’s possible that a rope trick is the true explanation for the mysterious event, but I think the much more interesting and clever method inspired by children’s folklore practice is the more likely and textually supported explanation.

What About Salem?

What do the stories of Mercy Short and Margaret Rule, two Boston girls who were not accusers in the Salem witch trials, have to do with the Salem question? First, they matter because, as I stated in the introduction, they bear heavily on the question of Cotton Mather, which is close to the heart of Salem scholars, whether they admit it or not. Second, they are so near in time and culture to the Salem tragedy that they shed light on it, just as do the case of the Goodwin children in 1688 and the Littleton children in 1720, neither of which I have included in this introduction. Burr (1914) puts it,

The importance of the [Mercy Short] narrative lies not only in its contemporaneity with the Salem trials and the side-lights it gives us on that episode and its environment, but yet more in the clearness with which it shows just what its author stood for in the matter. To him the case of Mercy Short was not only identical in kind with those of “the Bewitched people then tormented by Invisible Furies in the County of Essex”: it was itself one of those cases.

Burr’s point is illustrated by Cotton Mather mixing together the events in his Life of Phips, describing Boston and Salem tricks as all part of the same phenomenon.

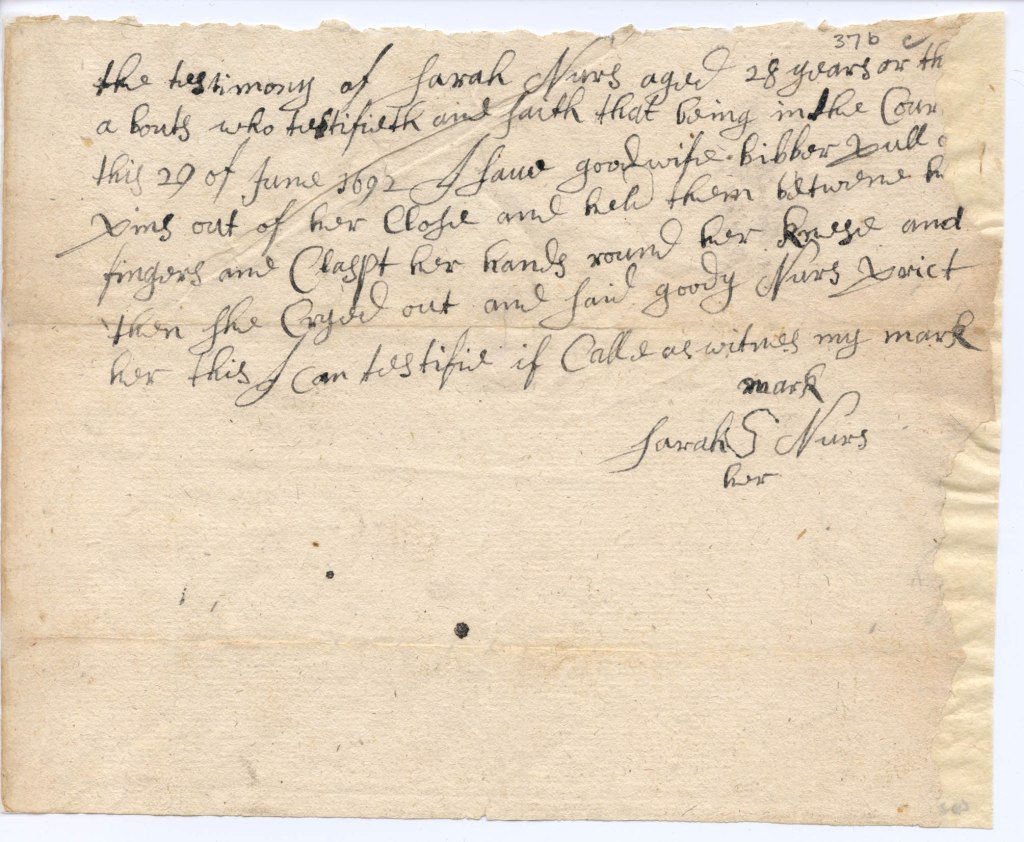

The same fraudulence and collusion detectable in the behavior of Mercy Short and Margaret Rule is also clear from the records of the Salem accusers. In addition to the rope trick mentioned above, here is the original handwritten testimony of Sarah Nurse regarding the poorly-executed magic trick attempted by Sarah Bibber, accusing Bibber of hiding pins and sticking herself with them to pretend to be afflicted:

I hope to write more about the Salem tragedy, which is why I have labeled this an introduction, but for now I will close with a little recommended reading list, in case the reader is interested in exploring the juicy Salem drama.

One thing that makes Salem the ultimate metaphorical source that other things are compared to, and what makes it rewarding to hobbyist scholars, is that it’s so small. A single person could never hope to be a master of the Cultural Revolution, or the Satanic Panic and related prosecutions of the 1980s and 90s, because in each case there are millions of pages of primary sources spread out over an entire country. But all the primary sources for Salem amount to only a few thousand pages. A solo hobbyist with spare time could learn them in a year, and begin to put them in context by casting a wider net.

The orthography of the late 17th century takes a while to get used to for modern English speakers, but the language is similar enough that it becomes easy to feel the character and personality behind the pen. These people are worth meeting and knowing, even Cotton Mather, and anyone can join the conversation that has been taking place for over three hundred years. The following lists collect some of my recommendations for where to get started in the conversation, with all eras represented.

Cotton Mather Opps, Haters, Alogs, Critics, Detractors, etc.:

Charles Upham, Salem Witchcraft and Cotton Mather: A Reply (1869). The first text I read on the topic, that instantly caused me to become obsessed. Beware!

Robert Calef, More Wonders of the Invisible World (1700). Part Discord leak, part drama callout. Calef’s strategy of printing the exact words of his opponents is laudable. He seems to have truly endeavored to get their best case out of them, so that he could address it, but they never offered much of a case. An interesting read not just for knowledge about Salem, but for a model of how to deal with liars and manipulators. I link a section of the Wikipedia page rather than a single edition because it contextualizes your options for which edition to read (another option is just to download the Burr narratives, linked below, and read it there). The Wikipedia and much of its archived Talk page appear to be written in part by a fellow Cotton Mather alog.

Charles Upham, Salem Witchcraft (1867). It’s a thousand pages long, but it doesn’t feel like it. The first volume is a history of Salem itself, so that when the tragedy in the second volume comes, its weight can be felt. Upham also reprints many useful sources, such as Deodat Lawson’s narrative (a different version from the one published in Burr, below) and various church record entries written by the minister Samuel Parris. (Say what you will about Cotton Mather, but Samuel Parris was a much worse villain in the tragedy.) Upham’s comments about Cotton Mather are mostly relegated to a footnote, which is what triggered Poole to write his review, which in turn triggered Upham to write his 91-page reply close-reading Cotton Mather’s devious prose, a project I hope to expand on at some point.

George Lincoln Burr, Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases, 1648-1706. (1914). Free download in the format of your choice. A valuable compendium of sources, including Cotton Mather’s books about the Goodwin children (before Salem) and Mercy Short (after Salem), Calef’s book including the Margaret Rule narrative, and much more, often with relevant diary entries and context in the notes. He reprints one of the most important documents, Thomas Brattle’s anti-witch-trial letter circulated with only his initials, from 1692 (page 167); both the argument and its author would influence Robert Calef in his work. An excellent choice for your first book on Salem.

George Lincoln Burr, New England’s Place in the History of Witchcraft (1911). A brief but deep synopsis of what made the 17th century witchcraft belief historically unusual, and a measured response to some Cotton Mather sweeping.

Mather-Calef paper on witchcraft. Written in 1694 from Cotton Mather, who is his own biggest opp, to Robert Calef, with the admonition to return it without copying it. This letter formed the basis for an important section of Calef’s text in More Wonders. Lost for centuries and found in 1914, it was published by the Massachusetts Historical Society, together with Calef’s own snarky little notes written in the margin.

Francis Hutchinson, An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft (1718). An engaging and frequently funny take on not just the Salem tragedy, but the history of witchcraft persecutions up to that point. Hutchinson was a Church of England minister, not an American, but it’s interesting to see what a person very close in time to the Mather-Calef beef made of it.

Thomas Hutchinson, The history of the province of Massachusets-Bay (1764-1767). Hutchinson, who served as Governor of Massachusetts, had a close family connection with the Mather family, his sister having married Cotton Mather’s son. He is polite about avoiding having Cotton Mather’s literal name in his mouth, but still roasts him in clearly identifiable ways (see Upham 1869, linked above, page 69, for examples). Hutchinson was born (in 1711) almost a generation after the events of Salem, but close enough in time for us to give deference to his impressions; also, he was working with a more complete set of records than later writers.

Cotton Mather Glazers, Sweepers, Dickriders, Defenders, Supporters etc.:

William Frederick Poole, Cotton Mather and Salem Witchcraft. 1869. The book review that Upham’s 91-page reply was written in reply to, see above. This is where he suggests that Margaret Rule really magically levitated. Poole also wrote a reply to Upham’s reply which I felt to be a personal attack:

William Frederick Poole, Witchcraft in Boston. Chapter IV of The Memorial History of Boston (1881). Begins on page 131. The narrative of Mercy Short, as told by a Cotton Mather fan—which is to say, with all the fun stuff edited out.

Wendell Barrett, Were the Salem Witches Guiltless? (The talk was presented in 1892, though the book was published in 1893. Begins on page 65.). Another example of an author who feels compelled to defend Cotton Mather by arguing that the Salem witchcraft was real, and that at least some of the executed deserved to die, like Poole drawing an analogy to 19th century Spiritualist practices.

George Lyman Kittredge, Notes on Witchcraft (1907). Excusing Cotton Mather from responsibility by arguing that the witchcraft belief was ubiquitous through all time, that everyone always believed in it, and that Cotton Mather was not particularly a moral entrepreneur who attempted to “get up” witch persecutions. This is the text that Burr (1911) is replying to.

Thomas J. Holmes, The Surreptitious Printing of One of Cotton Mather’s Manuscripts (1925). Useful as a brief synopsis of the sweeper case. Especially amusing for the insults and invective thrown at Robert Calef. Holmes, like Poole, was a librarian, but Holmes was more specifically the librarian of William G. Mather’s library, William G. Mather being an industrialist who was a direct descendant of Cotton Mather’s uncle, Timothy Mather (brother of Increase).

Chadwick Hansen, Witchcraft at Salem (1969). Easily the worst book about Salem that I have ever read, and one of the worst books on any subject I’ve ever forced myself to read, and I hate-read Francesca Gino’s book. Hansen is a Mather dickrider of a caliber not seen since Poole, and argues that not only was witchcraft real, the witches deserved to be hanged, and hanging was a lenient sentence. He carefully avoids mentioning any evidence that does not support his outlandish theory. I read some of his other work, which was much more interesting and reasonable. In his other work, he made one tiny reference to a specific trickster cultural practice, that is, speaking in such a way that outsider listeners are not able to understand what one is up to, so I cling to a fantasy that his book was a joke that nobody got, and when it ended up being his most popular work, he couldn’t exactly reveal the truth. It’s full of credulous claims of sketchy psychological and folkloric phenomena that had me fact checking him like he was a bad science twitter account. Terrible book, but a lot of fun for a banana.

Fence sitters:

Bernard Rosenthal, Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt (2009). A compendium of all the trial documents ever collected from Salem and the nearby towns that the witch trials spread to, all in one tidy volume. (You can get earlier versions for free, such as W. Elliot Woodward’s two-volume set Records of Salem Witchcraft printed in 1964, or the University of Virginia online repository which includes images of the original handwritten records, but Rosenthal’s edition is admirably complete and handy to have.) The introductory essay rushes to assert Cotton Mather’s innocence and good conduct (leading off with “Mather was instrumental in containing the episode [of the Goodwin children], which claimed no victims other than Glover, convicted of witchcraft and executed.” is certainly not a choice I would have made after reading Mather’s entire account in Memorable Providences). Rosenthal also praises Chadwick Hansen’s work, which I also find inexplicable, but he at least acknowledges the fraud committed by the accusers. Placing him in this category is more of a statement about how extreme the Cotton Mather sweepers get than about his apparent allegiance.

Emerson Baker, A Storm of Witchcraft (2015). Possibly the only recent history that didn’t trigger me to have a tantrum like Mercy Short in church. Avoids taking a side without particularly sweeping. Extra points for pointing out that psychological theories for the accusers’ behavior are controversial, rather than pretending, as some do, that a psychological theory is the consensus.

Thank you to my friend Curtis Yarvin, who introduced me to the story of Robert Calef, and who was brave during the scary time.