This appendix to “A Case Against the Placebo Effect” reviews the studies in the Sauro and Greenberg (2005) meta-analysis on the effect of opioid antagonists on placebo analgesia, in alphabetical order. Next, the relevant sizes of the study arms for each study are provided. Finally, research into the “placebo effect” in depression is reviewed.

Brief review of every study in Sauro and Greenberg (2005)

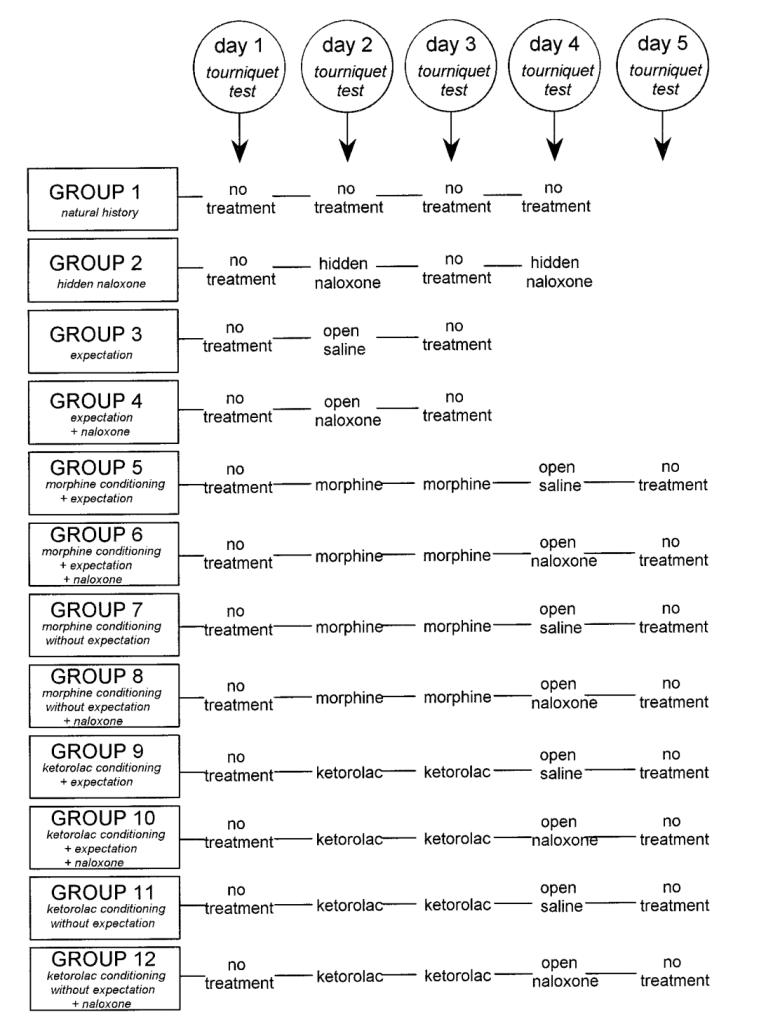

The first study is Neuropharmacological Dissection of Placebo Analgesia: Expectation-Activated Opioid Systems versus Conditioning-Activated Specific Subsystems (Amanzio and Benedetti, 1999). This, like many of the studies here, is a conditioning study, so it’s worth taking some time to explain what differentiates a conditioning study from a normal placebo study.

In a typical placebo study, a subject might be given a pill or cream and told it is a powerful pain reliever, whereas a control subject might be told that it is an inert pill or cream. In a conditioning study, subjects are trained and kind of gaslit with a conditioning procedure. For example, let’s imagine the placebo is a green light. The subjects are receiving electric shocks and asked to rate their pain. During the conditioning phase, they are given less intense, less painful electric shocks when the green light is on, and more intense, more painful shocks when the green light is off. They are told that the shocks are objectively of the same intensity. Basically, they are trained that green light means less pain. Afterwards, in the testing phase, they briefly guess wrong – specifically, they report less pain when the green light is on, at least until they realize that it no longer has any meaning. This is certainly deceptive, but I’m not convinced that this type of “conditioning” is what people mean when they say the placebo effect is real. Nonetheless, it is a common paradigm, because it is pretty easy to get subjects to essentially guess wrong, at least for a little while.

In Amanzio and Benedetti (1999), as in many of these studies, subjects were conditioned not with a green light, but with literal morphine (or, in a different arm, with ketorolac, a non-opioid NSAID pain reliever). The researchers induced ischemic pain in subjects with a tourniquet and had subjects squeeze and hand exerciser over and over until they could no longer bear it, and subjects given morphine unsurprisingly could bear it for longer than they had when given nothing. The equivalent of the “green light” was the injection, indicating that morphine had been given. The conditioning continued for two days. Then, on the third day, some subjects received an injection of saline, but were told it was morphine, and were able to last somewhat longer than baseline in the ischemic pain test (though not, it seems, as long as with real morphine). The authors claim this worked even when the subjects were told it was an antibiotic, not morphine, though not as much. The next day, there was no injection, and pain tolerance returned to baseline. (That is, subjects guessed correctly again.)

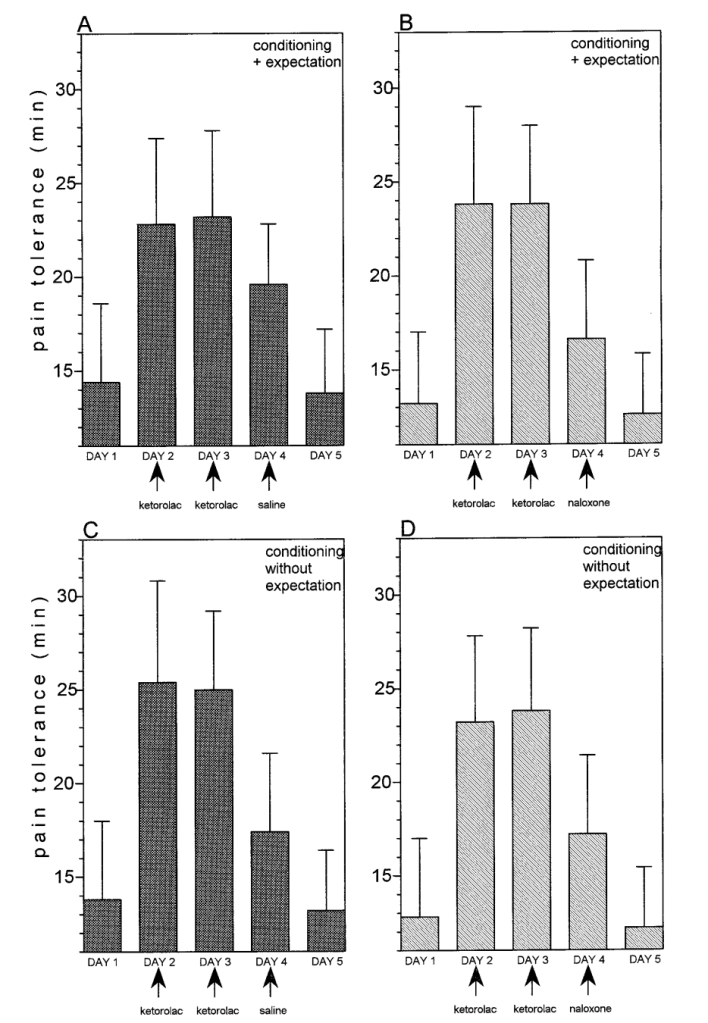

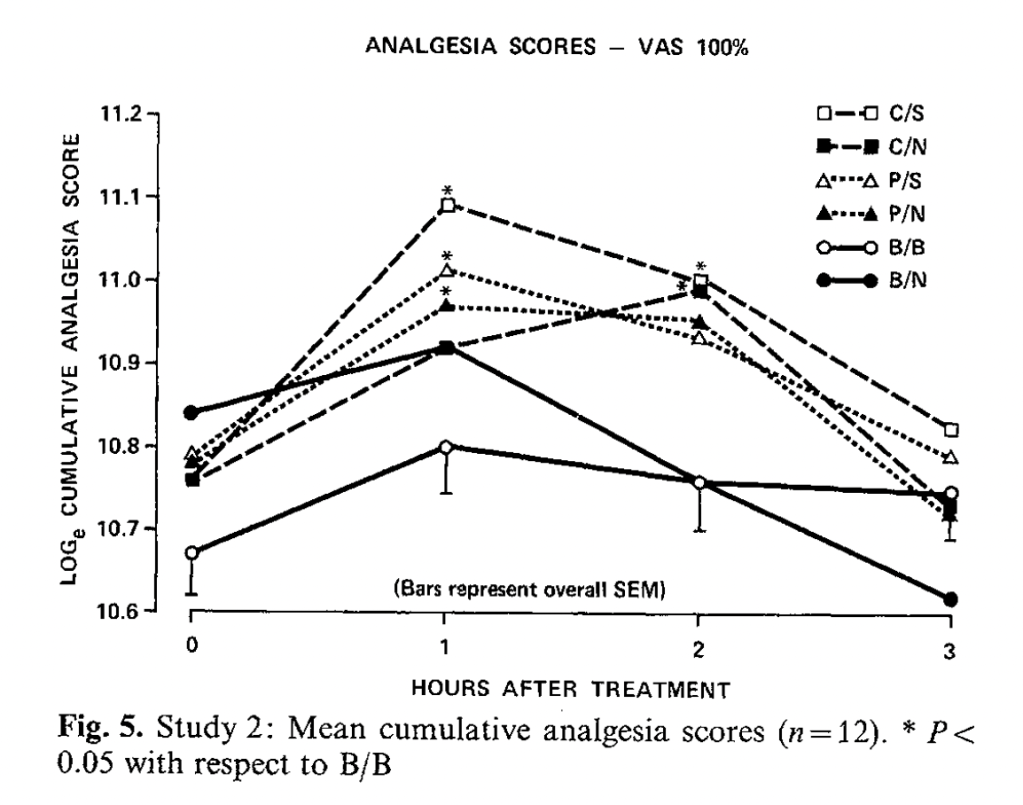

However, if instead of a saline injection said to be morphine, subjects were given a naloxone injection, their morphine conditioning did not work, according to these authors, and pain tolerance again went back to baseline. When conditioned with the non-opioid drug ketorolac, however, the (conditioned) placebo response was not extinguished with naloxone, and subjects could squeeze the hand exerciser as long as they could with a saline injection. Here are the graphs for morphine conditioning – baseline is day 1 (no treatment), days 2 and 3 are morphine conditioning (they squeeze the squeezer for a long time), day 4 is either saline or naloxone described as either morphine (+ expectation) or an antibiotic (without expectation), and day 5 is baseline:

And here are the graphs for ketorolac, with very little apparent effect of naloxone vs. saline:

In some ways, this is a more interesting finding that simply “the placebo effect is about endogenous opioids.” This experiment purports to find two separate kinds of placebo effects, depending on the drug used for conditioning, one destroyed by opioid antagonists, and the other remaining perfectly intact! This does not seem like evidence for a general role of endogenous opioids in “the placebo effect.”

Another finding in this many, many-armed study is that hidden injections of naloxone in the absence of conditioning do not affect pain tolerance. That is, whatever endogenous opioids may be produced in response to pain naturally, naloxone does not seem to affect them – only placebo-generated endogenous opioids?? This finding has been somewhat contested; some authors have even found that opioid antagonists cause “paradoxical” pain relief!

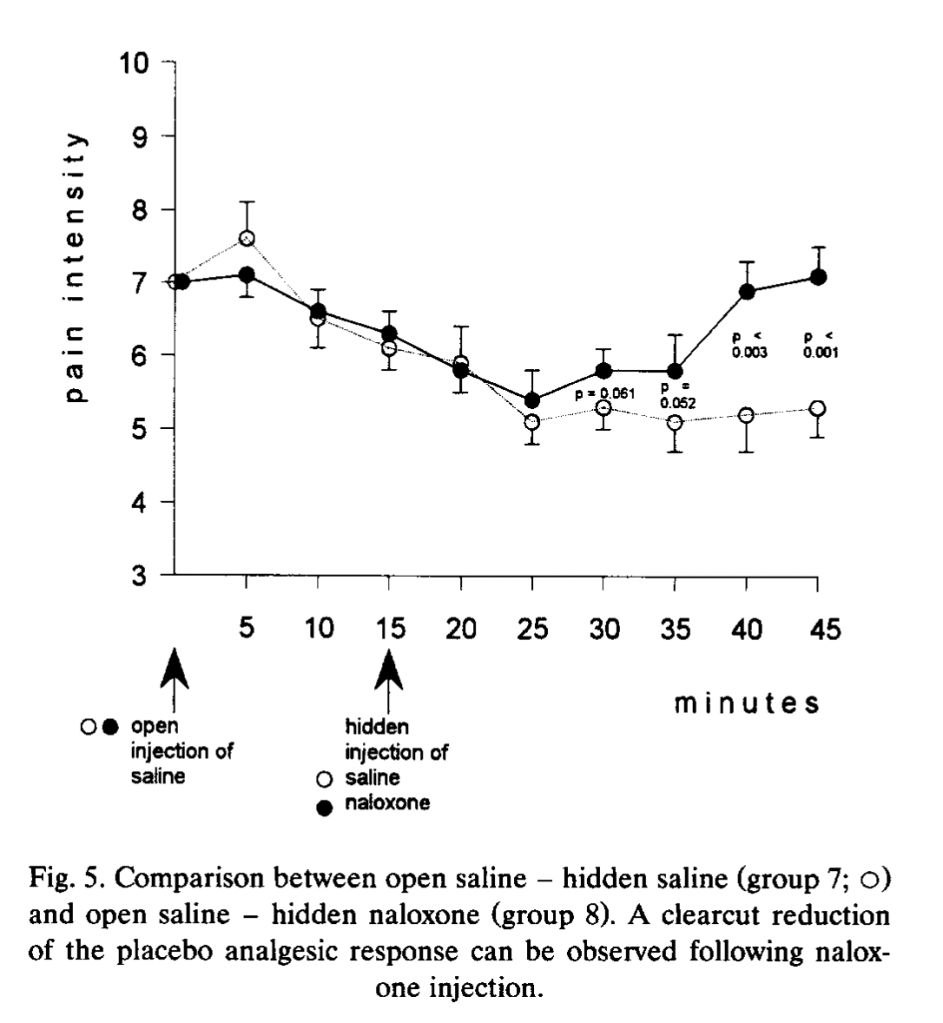

The second study is Amanzio et al. 2001, Response variability to analgesics: a role for non-specific activation of endogenous opioids, also with Benedetti as a co-author. The authors seem to throw the results of the previous study in the garbage, now attempting to show that endogenous opioids are involved in pain relief from ketorolac, too. With a study design that I personally find very tedious, they start with a population of clinical pain patients recovering from thoracic surgery. They found that the dose of drugs needed to achieve a 50% reduction in self-reported pain was much higher when the injection was open (in view of the patient), rather than hidden. As someone who doubts that pain intensity reports are a pure measure of pain experience, and have at least some component of politeness, roleplaying, and judgment of situational appropriateness, it is not very surprising that patients who are aware they have been treated report less pain that patients who are not aware of any treatment. These authors interpret this as part of the placebo effect. Specifically, they say, “the difference between open and hidden [doses to relieve 50% of pain] may be taken as a measure of the placebo effect.”

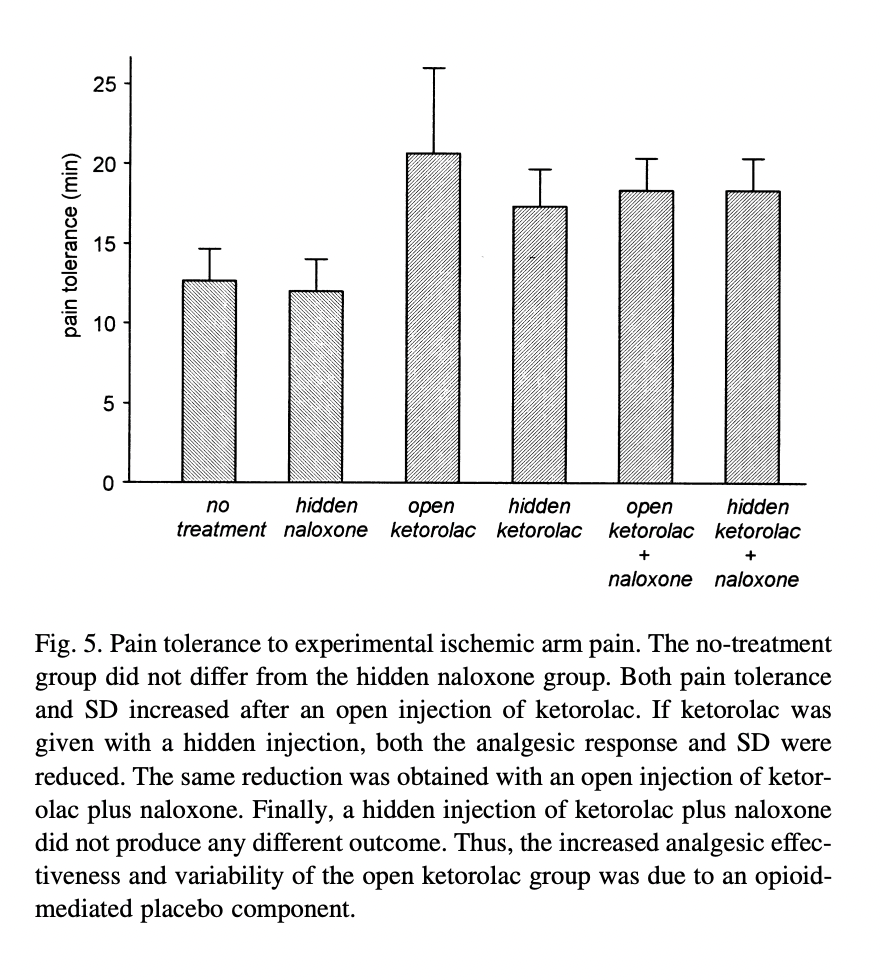

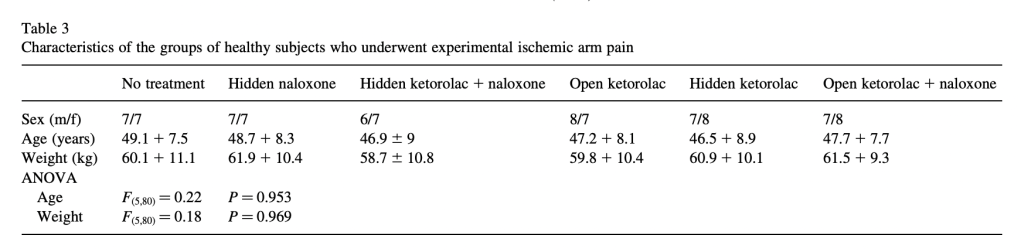

They also focus on the finding that the dose needed to achieve 50% pain relief was not only larger, but less variable in the hidden injection groups. They then introduce an experimental group of healthy subjects, who are again going to get various injections and wear a tourniquet while squeezing the hand exerciser until they can’t stand it anymore. Here are their results:

They are focusing on the difference between open ketorolac (the highest squeezy test times, at about twenty minutes, a little lower than their previous groups) and the three conditions to the right. Their claim now is that naloxone reduces the “placebo effect” component of the open ketorolac injection. They emphasize the small (but apparently statistically significant, with only 15 subjects per arm) difference between the open ketorolac and the hidden ketorolac, and say that “the effects of a hidden injection of ketorolac and an

open injection of ketorolac plus naloxone were exactly the same.” (Although I must say, visually, open ketorolac plus naloxone looks about in between the open ketorolac and hidden ketorolac.) The addition of naloxone seems to remove the difference between the open and hidden injections in their sample, thereby, in this tedious and roundabout way, demonstrating that it extinguished the placebo effect component of a non-opioid drug.

They also show that their subjects’ time in the tourniquet varied more in the open ketorolac-no naloxone condition than in the other conditions, suggesting that part of the variance is placebo effect, and naloxone removes this:

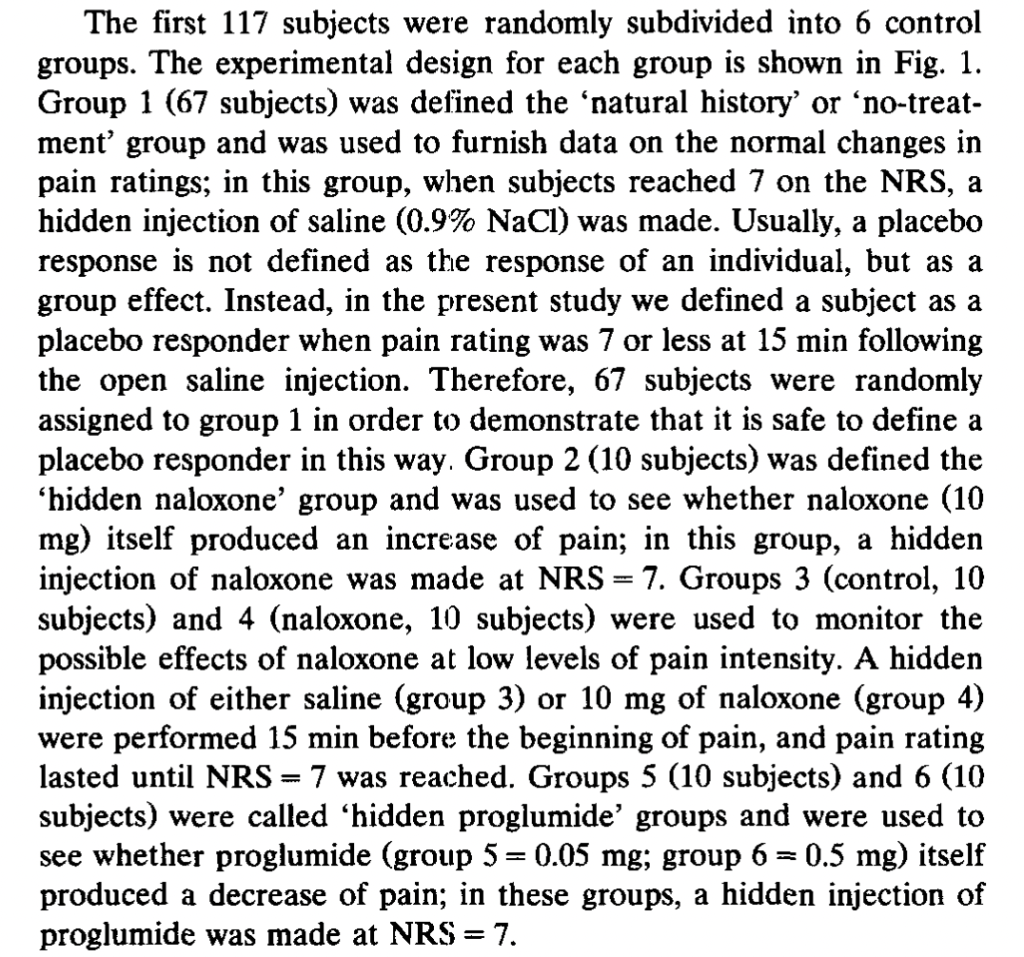

The third paper is an earlier paper by Benedetti as the sole author, The opposite effects of the opiate antagonist naloxone and the cholecystokinin antagonist proglumide on placebo analgesia (1996). Subjects again have their forearms wrapped in painful tourniquets and squeeze a hand squeezer until they can’t stand it anymore (which, I might add, is a voluntary act), although here subjects are also rating their pain intensity (a more typical self-report measure).

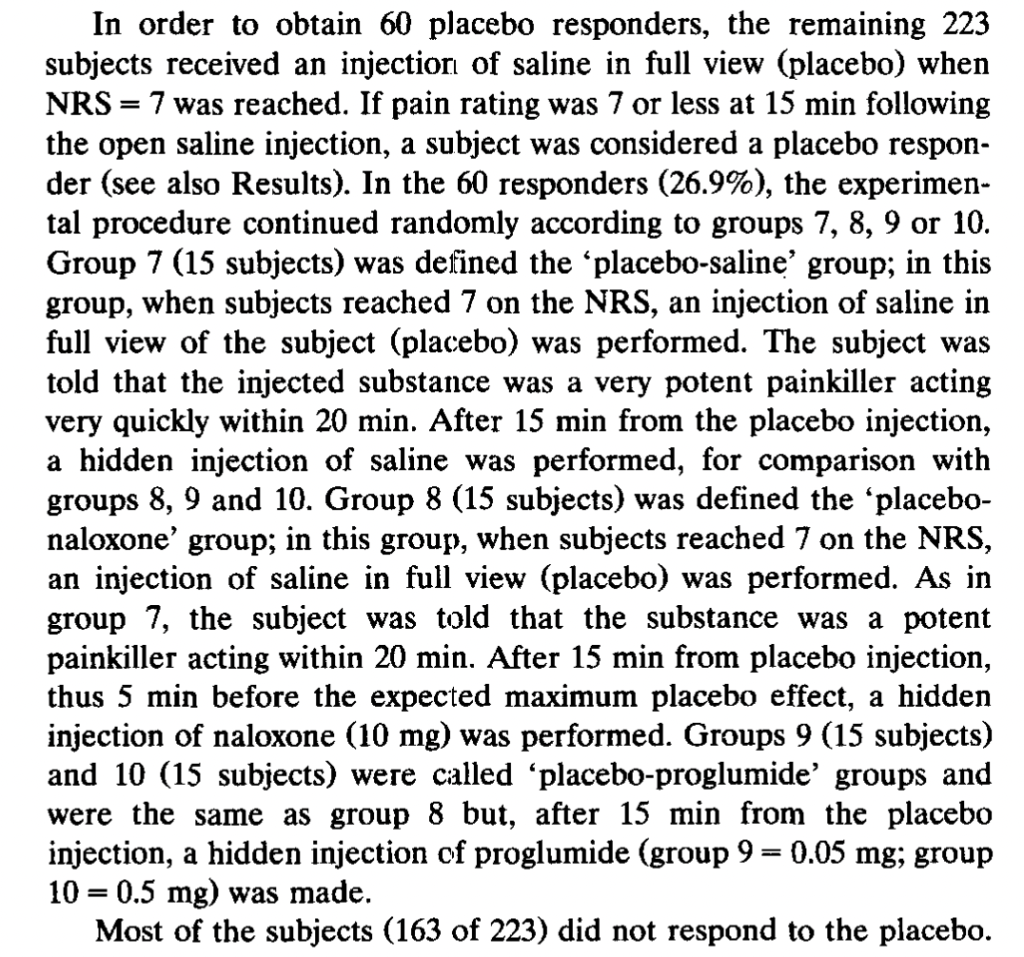

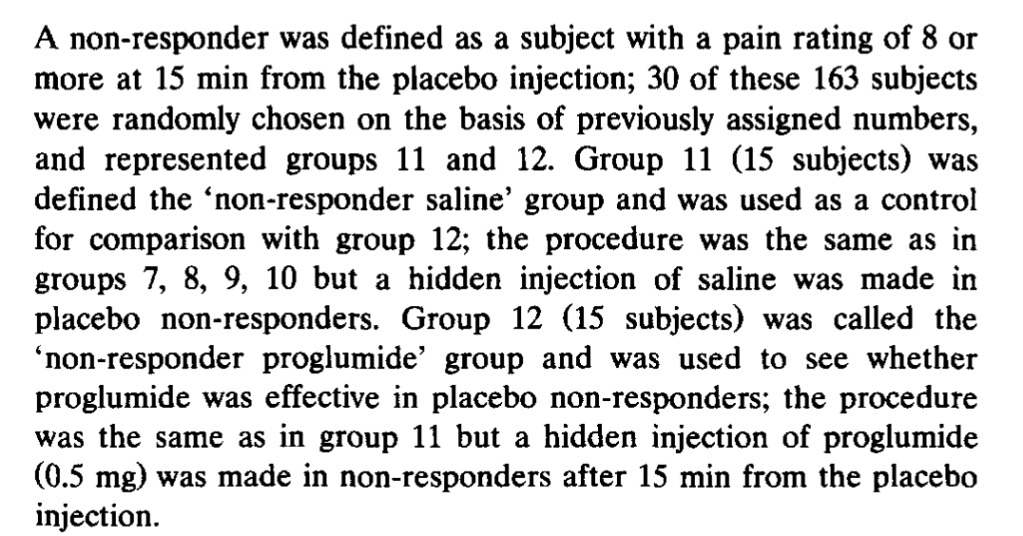

Interestingly, they construct a group of “placebo responders,” a procedure criticized in the section of the main post called Run In, Wash Out. They say: “In order to obtain 60 placebo responders, the remaining 223 subjects received an injection of saline in full view (placebo) when [a pain intensity rating of] 7 was reached. If pain rating was 7 or less at 15 min following the open saline injection, a subject was considered a placebo responder….Most of the subjects (163 out of 223) did not respond to placebo.” There are also a separate 117 subjects assigned to control groups. These subjects are divided between twelve separate experimental conditions, with between 10 and 67 subjects per condition.

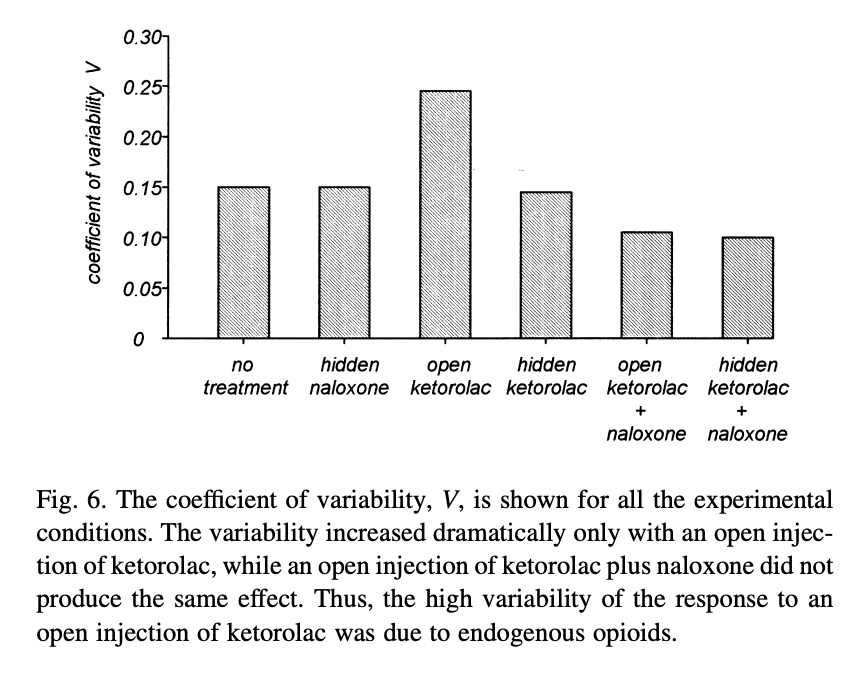

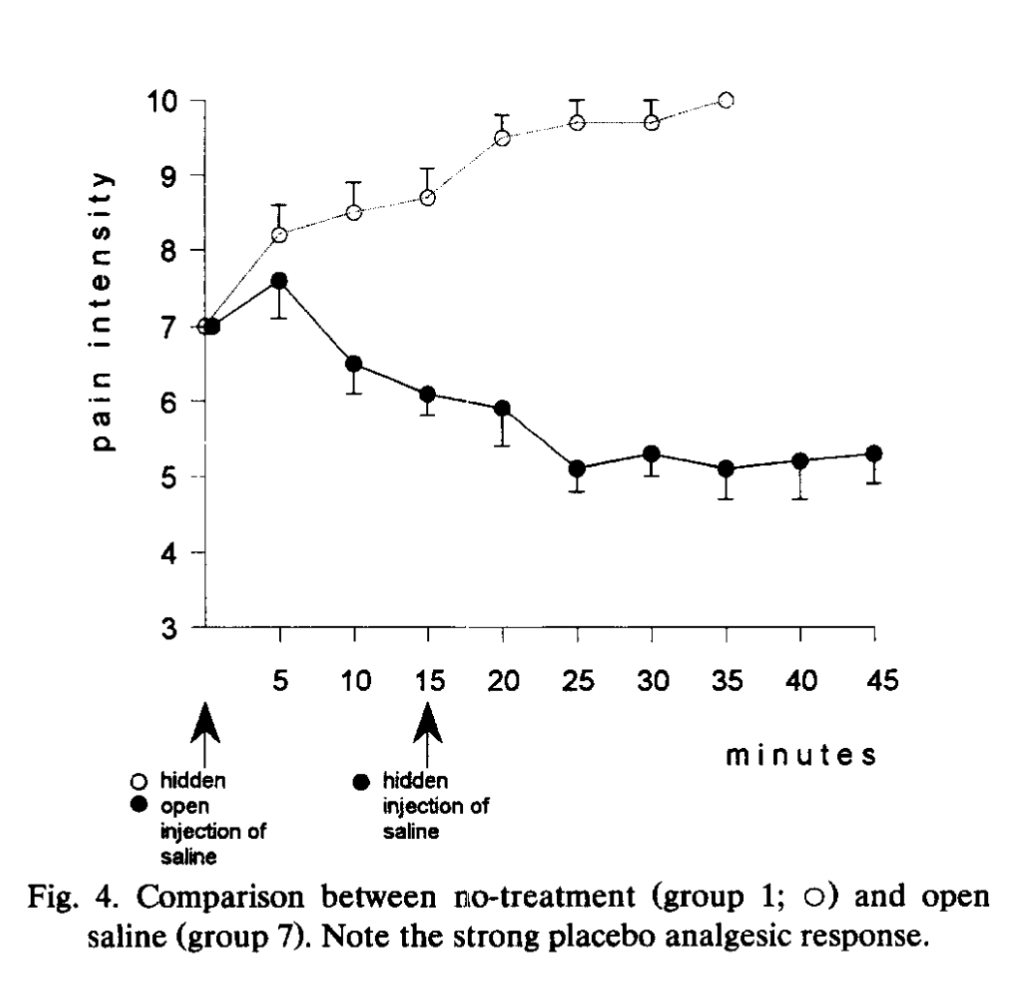

In this experiment, among two of many other groups of subjects, an injection of saline (that subjects are told is a potent painkiller) is given at the start of the squeezy test when pain reaches a 7 (which typically takes about 25 minutes), and fifteen minutes after that, a hidden injection (into an IV line that extended a meter into another room) of either naloxone or saline is given. Group 7 (15 subjects, composed of “placebo responders”) gets open saline (presented as a painkiller) at the start, and a hidden injection of saline 15 minutes in. Group 8 (15 subjects, also “placebo responders”) gets saline (presented as a painkiller) at the start, and a hidden injection of naloxone 15 minutes later. Here is how they do:

For ten minutes after the hidden injection of saline or naltrexone, pain ratings continue to decrease. At 25 minutes, when the subjects in the two previously-discussed experiments would have long since tapped out, there starts to be a difference between the two groups: the saline group stays flat at a pain rating between 5 and 6, and the naltrexone group begins to rise back to the initial pain rating of 7. Here is Group 7 compared to no treatment non-placebo-responders, who report an increase in pain and tap out at 35 minutes:

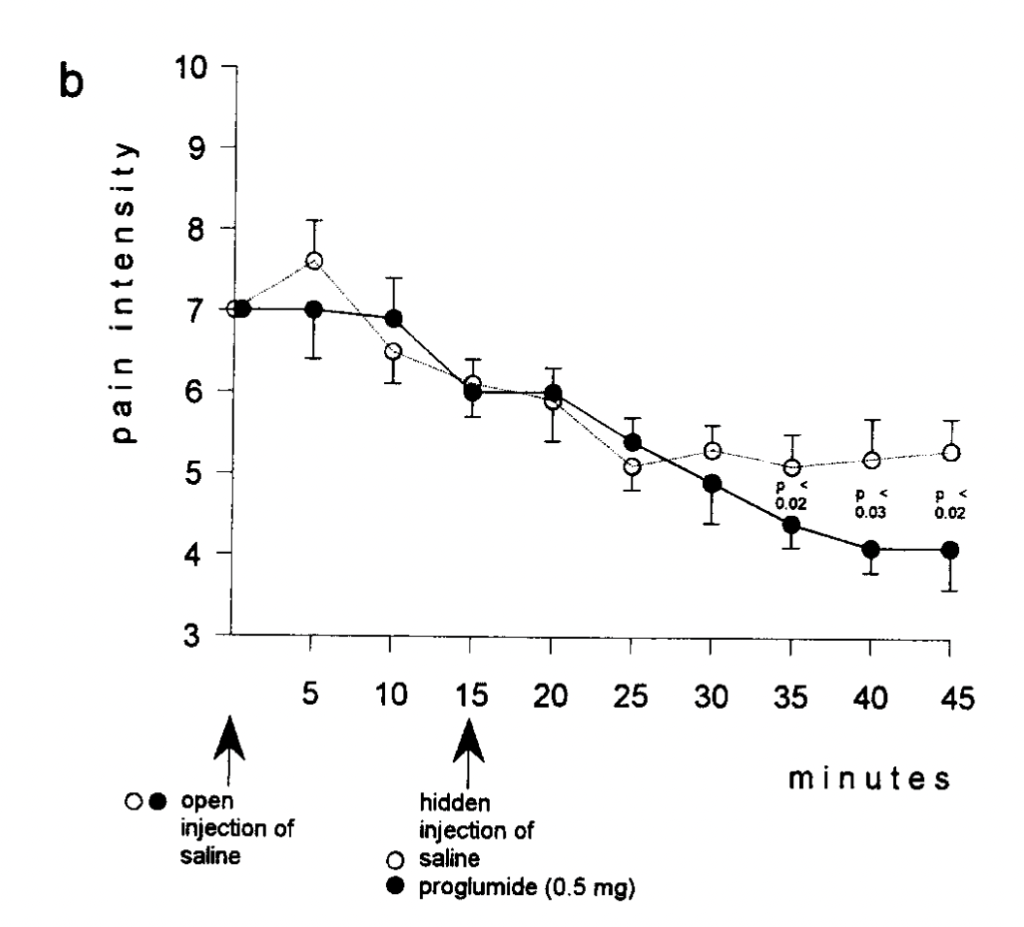

Group 7 is also compared to Group 10, who gets a hidden injection of the drug proglumide, a drug thought to increase the effects of opiates:

They get a “placebo-enhancing” effect when .5 mg (but not .05 mg) of the drug is given as a hidden injection, when subjects who have already been hanging out in a tourniquet setup squeezing the squeezer for 25 minutes continue to squeeze and rate their pain as only between 4 and 5 after 45 minutes of more squeezing. The author does note:

After 45 min from the first injection, the experiment was discontinued even if pain ratings were still low. In fact, by considering these 45 min plus the waiting time to reach [a pain rating of] 7, the experiment lasted more than 1 h. After this time, subjects reported to be tired and usually asked to discontinue the experiment even if their pain was not rated as unbearable.

The next paper is Somatotopic Activation of Opioid Systems by Target-Directed

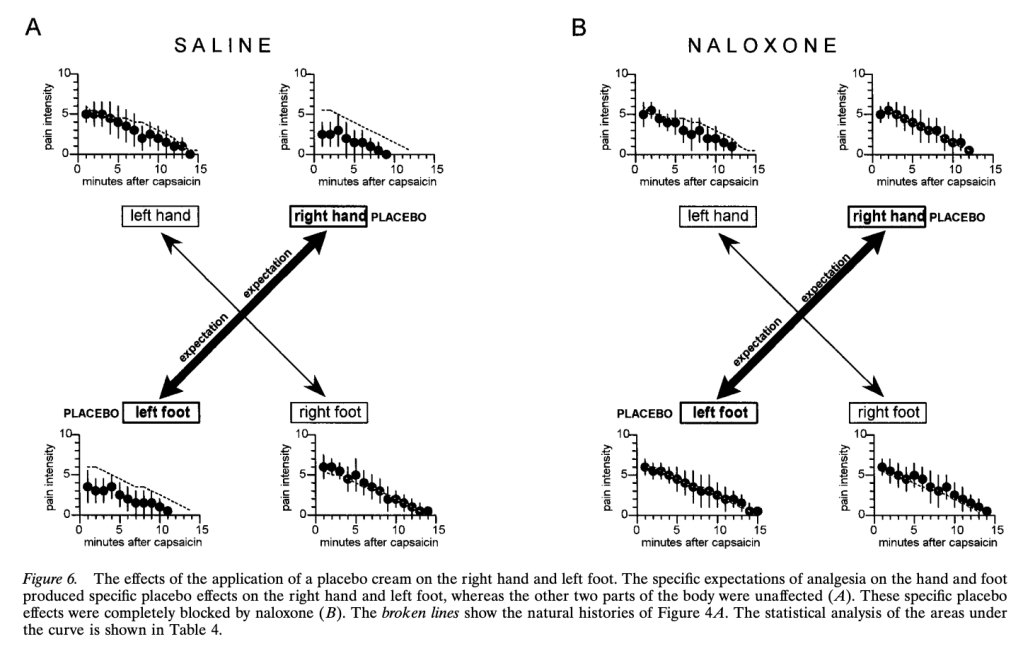

Expectations of Analgesia, by Benedetti et al. (1999). Here we get a break from the tourniquets and start doing subcutaneous injection of capsaicin into various body parts (hands and feet). Subjects were treated with a placebo cream that they were told was a powerful anesthetic, but only on one body part. “The specific expectation of analgesia on the left hand produced a placebo

effect only on the left hand and not on the other parts of the body,” the authors say. Further, “This highly specific placebo effect was completely blocked by naloxone.” The subjects gave lower pain ratings for the placebo-treated body part when injected with capsaicin, but not their other body parts similarly injected. However, subjects given naloxone did not give lower ratings for the placebo-cream-treated body part:

The authors also had a group of 20 subjects who received lidocaine cream rather than placebo, “to allow the double-blind design.” Unfortunately, the “natural history” control group is not reported to receive any kind of cream, so the “placebo effect” was that not just of suggestion of powerful pain relief, but whatever the cream itself may have contributed. Again, there was no effect of naloxone on the non-cream-treated natural history control group.

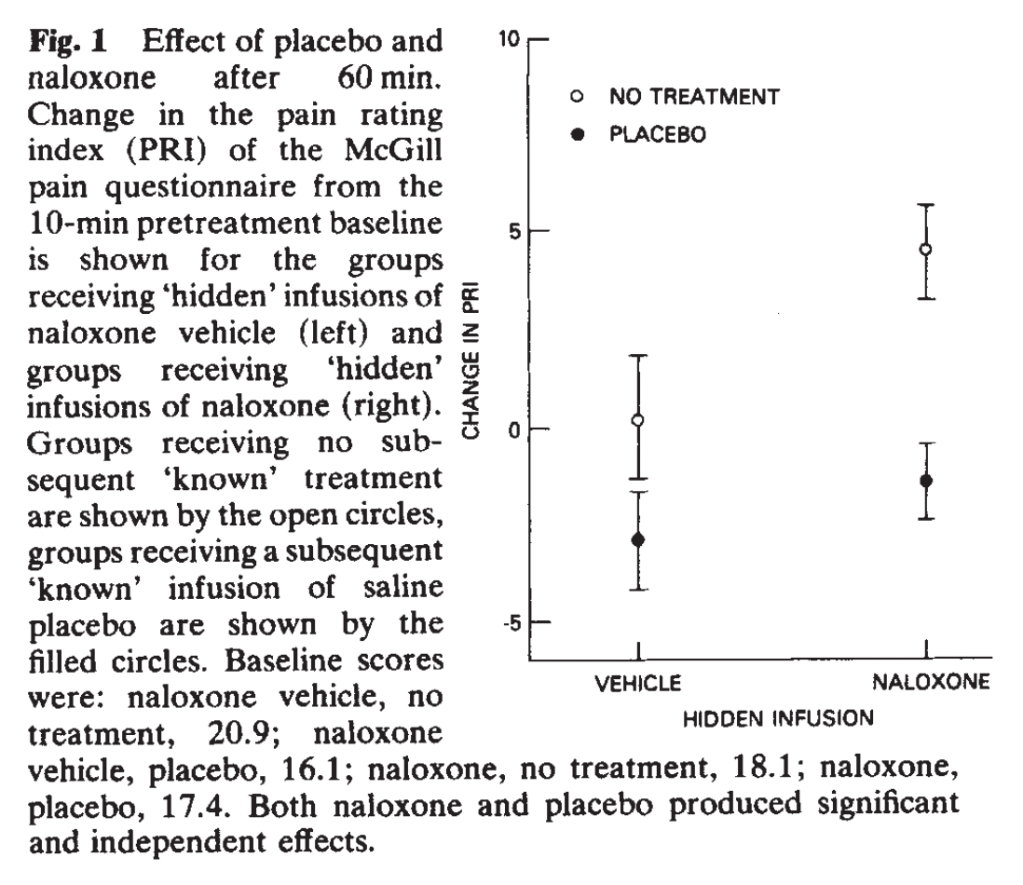

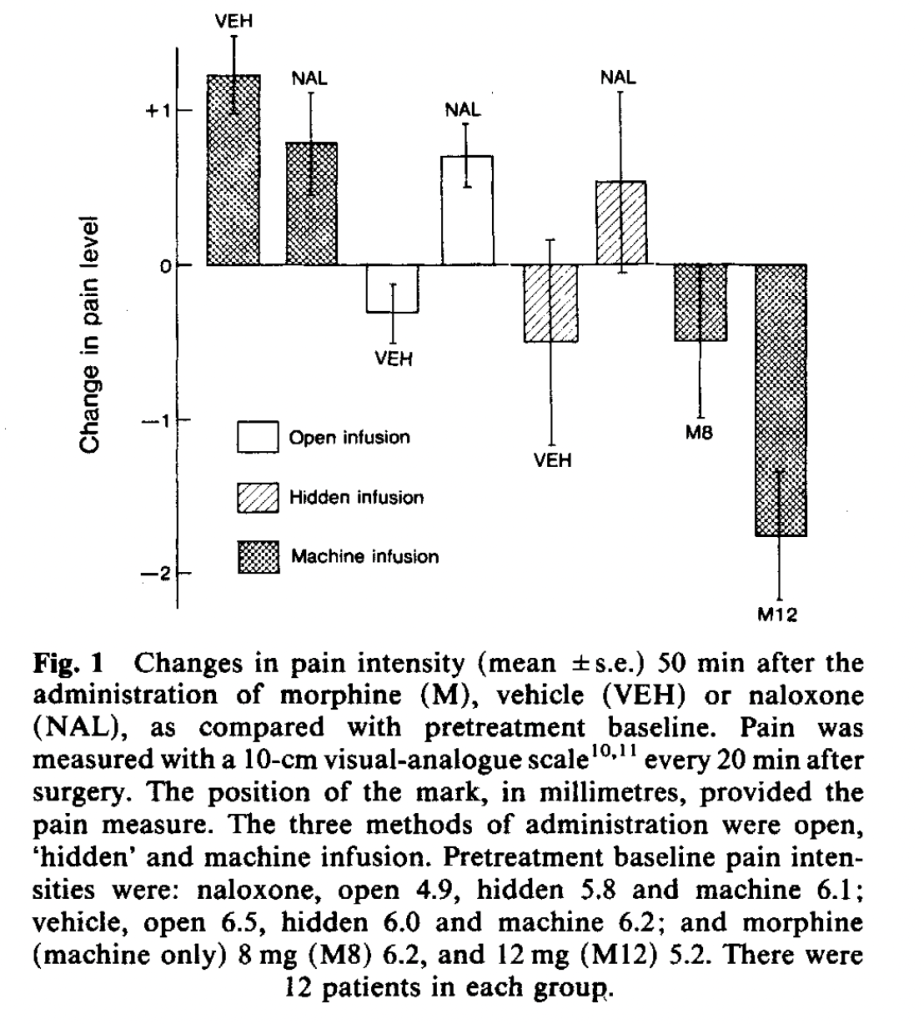

The fifth study, our first non-Benedetti study, is Gracely et al. (1983), Placebo and naloxone can alter post-surgical pain by separate mechanisms. Our subjects here are dental patients who just had their wisdom teeth out. Their instrument is the McGill Pain Questionnaire, which is a list of adjectives to describe various aspects of pain that translate into points (one point for flickering, five points for beating, two points for boring, three points for smarting, etc.) The maximum score is 78. The subjects were first given either 10 mg naloxone or placebo, and then treated with either fentanyl, placebo, or no treatment. They rated their pain on the McGill word scale 10 and 60 minutes before and after the treatment.

As for the fentanyl groups, their baseline pain was 17.44 (fentanyl only) and 16.88 (fentanyl but also got naloxone). Fentanyl alone reduced pain by 10.83 points at 10 minutes and 4.61 points at 60 minutes. Naloxone reversed the pain-relieving effects of fentanyl, decreasing pain by only .4 points at 10 minutes and increasing it by 2.8 points at 60 minutes.

The authors find effects for placebo treatment (getting a saline injection versus nothing), although smaller than for fentanyl. The “placebo effect” was also significant when the placebo recipients also got naloxone, but it was slightly smaller (filled-in circles):

Interestingly, the no-treatment group reported no change at 60 minutes after receiving a hidden placebo injection, but the no-treatment group reported much more pain after receiving a hidden naloxone injection. This is in contrast to the Bernedetti lab’s repeated finding of no effect of naloxone on natural history, a debate that will continue. The placebo group was polite as expected, experiencing a small and realistic placebo effect of perhaps 1-3 points on a 78-point scale. Naloxone seems to have caused a much greater difference for the no-treatment group than for the placebo group. They conclude, “naloxone hyperalgesia does not depend on placebo administration,” in contrast to the previous findings. They continue:

As this hyperalgesia is similar in the no-treatment and placebo groups, there is no evidence for an opioid component to placebo analgesia in this study. This finding suggests that naloxone hyperalgesia may involve the antagonism of endogenous opioid compounds released as a consequence of surgical stress. Although naloxone reverses stress analgesia, it has no effect on pain-free subjects…

“Stress analgesia” is the finding that if subjects are stressed out, such as by being forced to do math problems or public speaking, they will report lower pain ratings, as discussed in the main post.

So, we have our first non-Benedetti study, and the first failure to find naloxone extinguishing the placebo effect (especially compared to its effects on no treatment, much less fentanyl analgesia).

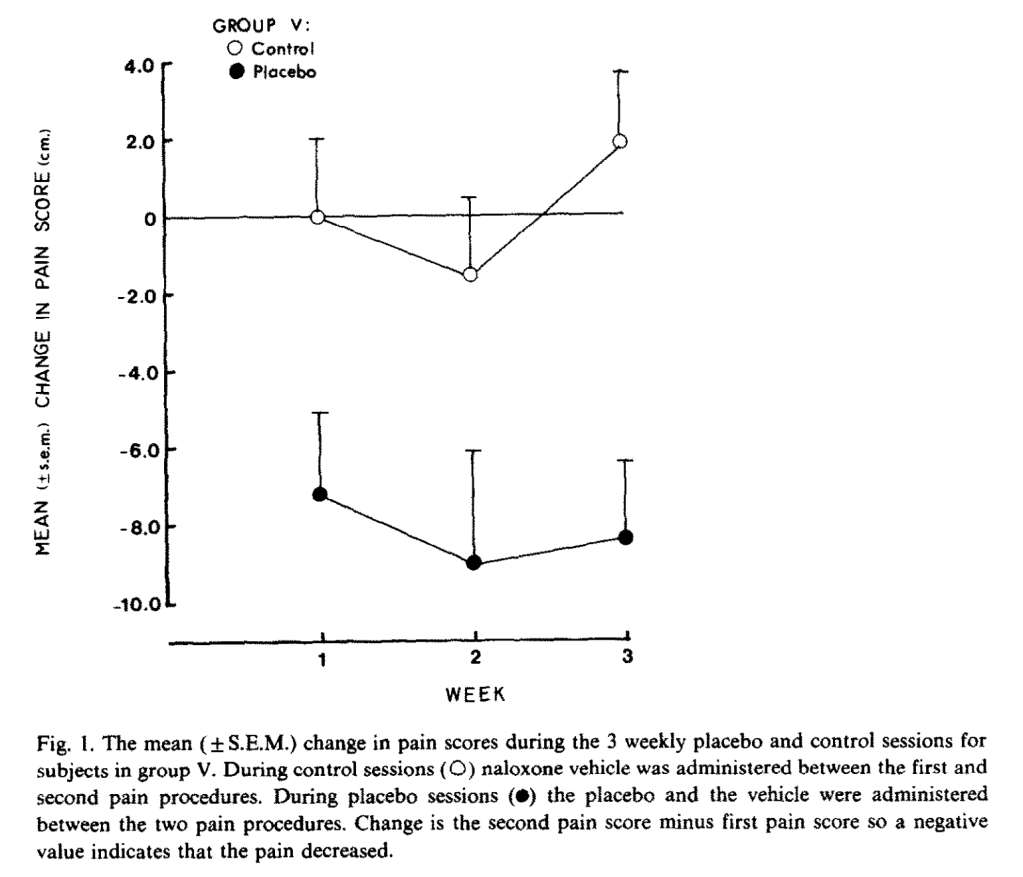

Sixth is another study from 1983, and another non-Benedetti study, Partial antagonism of placebo analgesia by naloxone, by Grevert et al. (1983). We are back to ischemic arm pain with tourniquets, and the authors use a 10 cm visual analog pain scale (which they do not say, but we can infer, is 0-100 points). During the tourniquet test, subjects rated their pain every minute for ten minutes. They showed up three times a week for three weeks, and underwent two pain procedures per day. The first procedure was always a control, with no injections or anything. In all sessions, subjects were hooked up to an IV apparatus, through which researchers could administer hidden injections. Only once per week, they received a placebo injection that they were told was a painkiller. (I’m not sure how the researchers justified setting up an IV line every session when no apparent injection occurred.) 40 minutes later, they received either naloxone or an inert substance in a hidden injection. On the other two “control” days, subjects did the regular control pain rating task and then received either a hidden injection of naloxone or the same inert substance, but no placebo. It took me way longer to figure out what was going on in this study than it took you to read this, but I apologize for how tedious it is. This is one of the most confusing studies I have ever read.

Subjects in the no-naloxone, hidden-sham-injection group demonstrated the largest decreases in pain ratings compared to their control sessions of about seven to ten points on a 100-point scale, versus the naloxone group, who seem to have a difference of between three and seven points compared to their control sessions. Here is placebo and inert hidden injection versus control sessions:

And here are placebo with naloxone versus their control sessions:

“The dependent variable is the change in pain score during the placebo session minus the change in pain score during the control session of the same week,” that is, (I think), not comparing pain scores, but comparing deltas of pain scores under different conditions. The authors assure us that the difference was statistically significant at p < .02. Therefore, we have our first (extremely confusing) non-Bernadetti result confirming that naloxone (slightly) reduces the (small) placebo effect.

Next we have Hersh et al. (1993), Narcotic receptor blockade and its effect on

the analgesic response to placebo and ibuprofen after oral surgery, another non-Bernadetti study. It is another study on patients experiencing pain after oral surgery. They tested ibuprofen, codeine, and placebo with and without naltrexone (another opioid antagonist), and collect an impressive array of measures of pain and drug efficacy.

Interestingly, despite collecting seven measures of drug efficacy, the authors could not even find a significant difference between subjects administered codeine (an opioid drug) with naltrexone (an opioid antagonist) and subjects given codeine and placebo. They also did not find any significant difference on any measure between placebo-naloxone and placebo-placebo, our second negative result for our third non-Benedetti study. The authors put this down to small sample size, despite their groups being of similar size to other studies reported. One of the only significant results that they could pull out, other than that ibuprofen was superior to the other treatments, was that naltrexone “significantly increased (p < .05) ibuprofen’s duration of action,” but I suspect that is just noise.

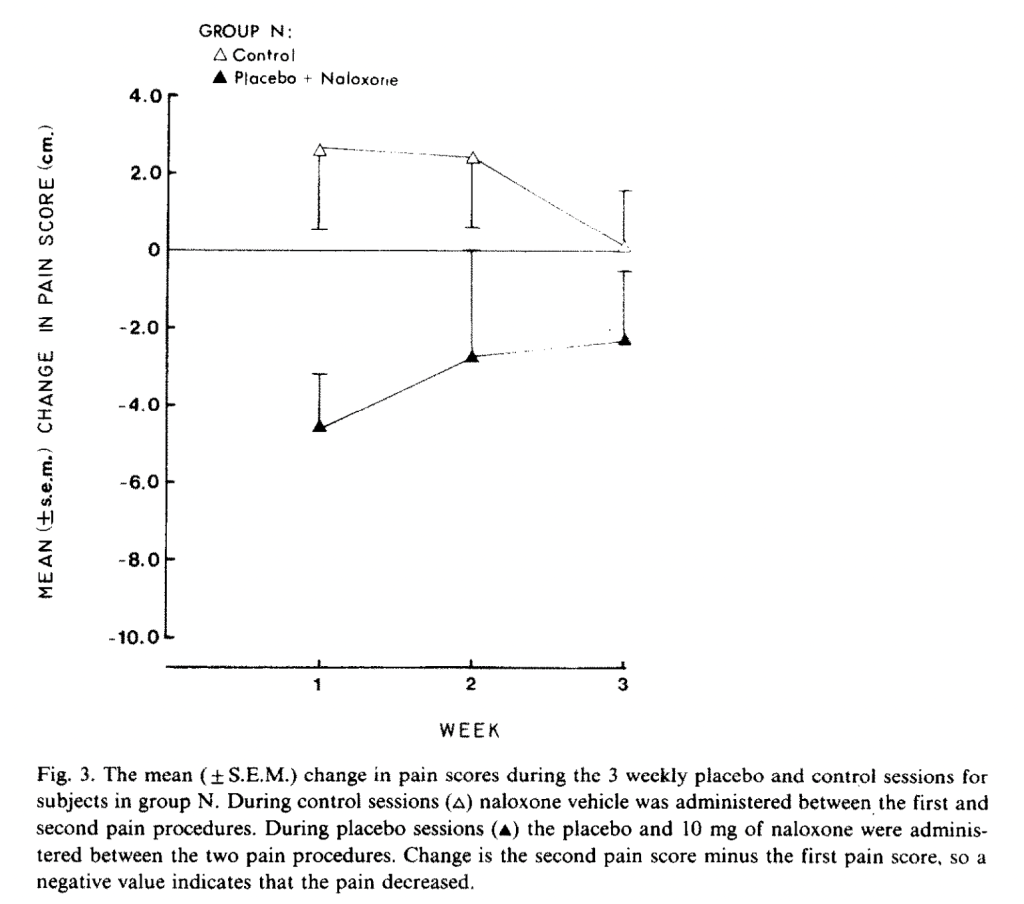

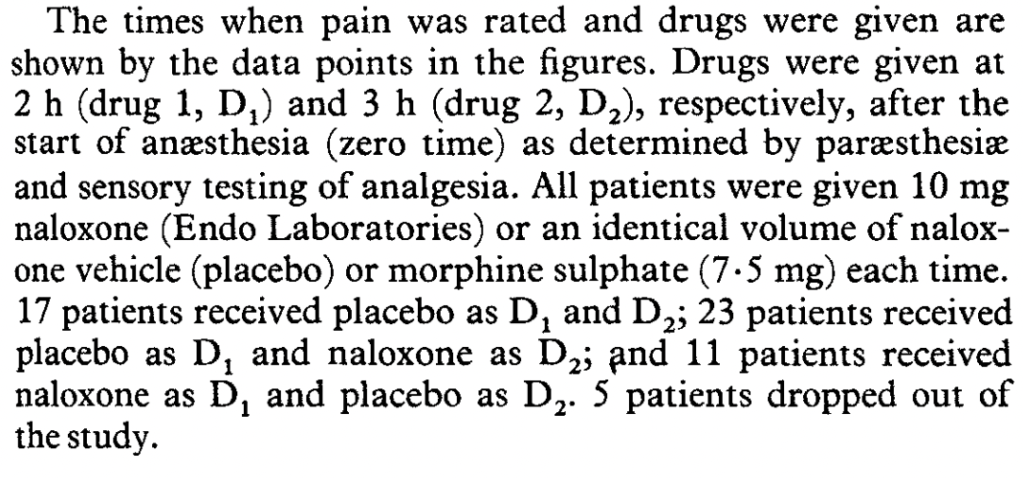

Next is Levine et al. (1978), The mechanism of placebo analgesia, the oldest study here and I believe the study that started it all. This is yet another study on oral surgery patients. They gave recovering patients injections at two hours and three hours after anesthesia, consisting of either morphine, placebo, or naltrexone for each injection, but only the results for placebo-placebo and placebo-naltrexone are reported. There results are summarized here:

They find a significant difference in pain ratings one hour after the second drug administration that is significant at p < .05 and looks suspiciously similar to the pre-existing difference between groups before any injection occurred. They further break down the subjects into “placebo responders” (n=11) and “placebo non-responders” (n=6) and find that naloxone only reduces the placebo effect in placebo responders.

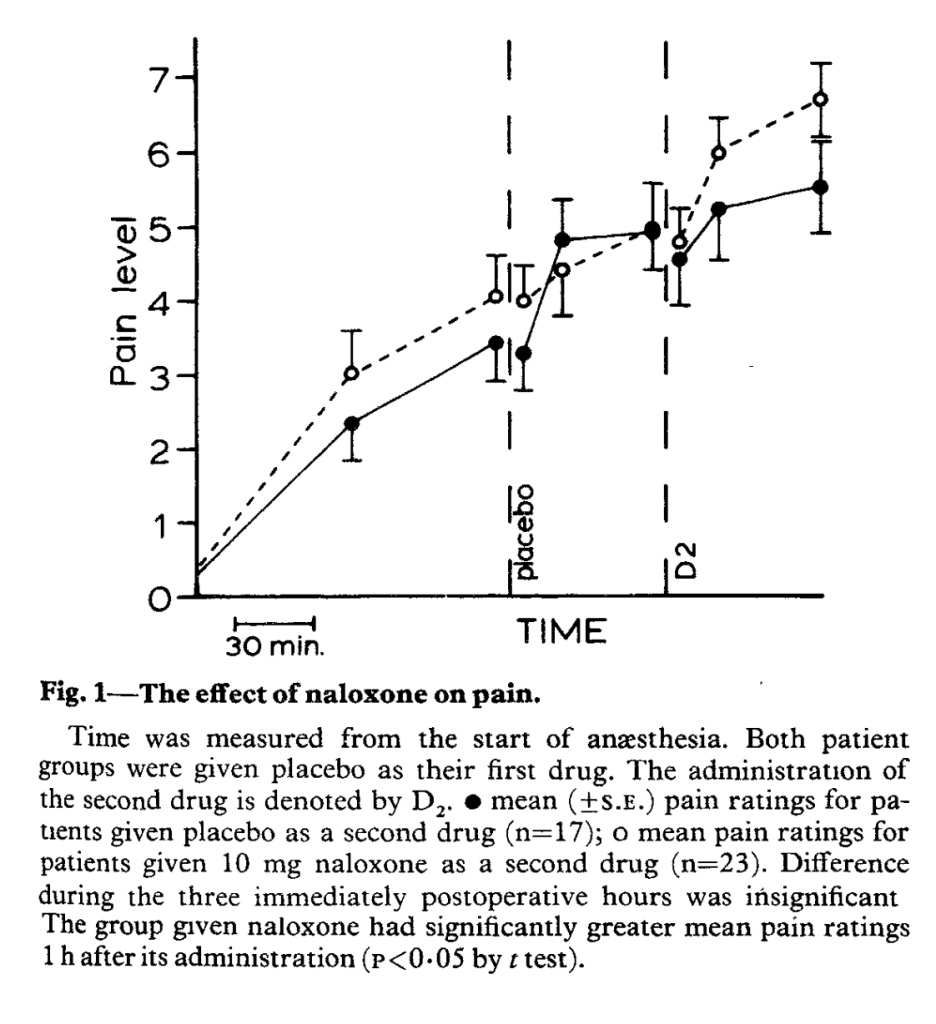

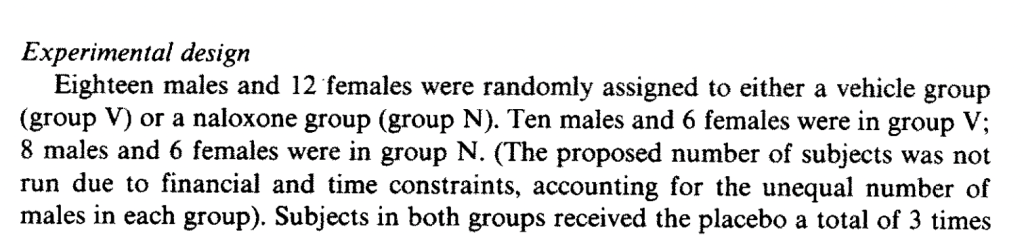

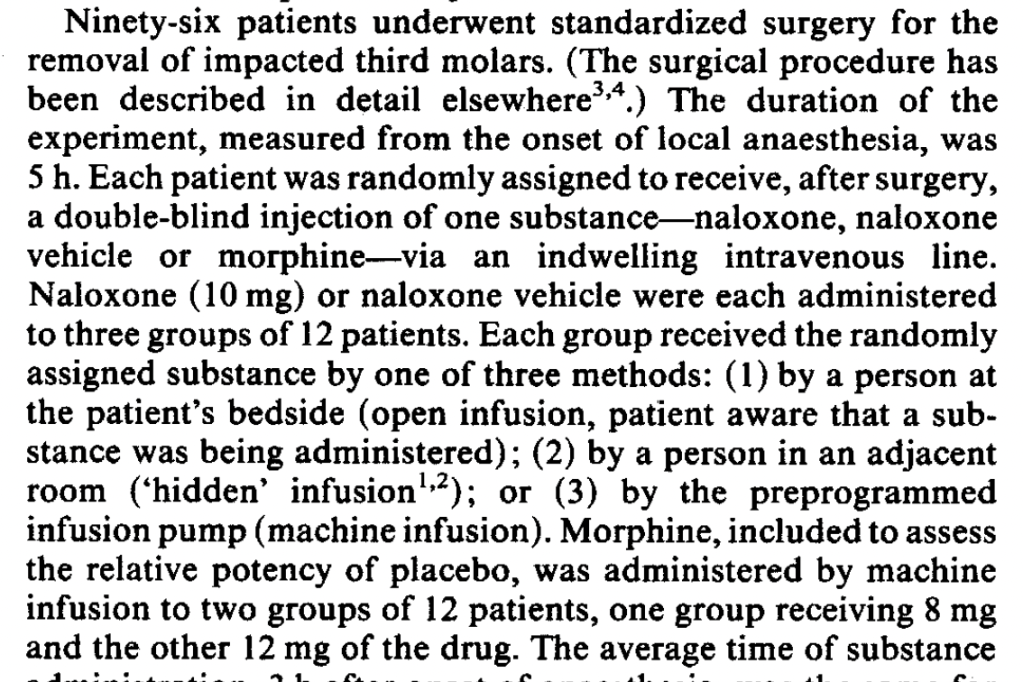

Next we have another study by the same team, Levine and Gordon (1984), Influence of the method of drug administration on analgesic response. They are embracing technology in yet another study of impacted molar surgery patients, comparing open injections, hidden injections by a human, and hidden injections by a programmable robot syringe pump. Each method was used for two substances: naloxone and a placebo. Morphine was injected by the robot machine in two doses as a comparison.

In most studies, researchers first establish some kind of “placebo effect,” and then try to demonstrate that naloxone reduces it. Here, the researchers only give each patient one injection, with one baseline pain measure and one subsequent pain measure 50 minutes after injection. They infer a placebo effect by comparing the different injection method-substance interactions.

Pain seems to have increased for the group given only a machine injection of an inert substance (VEH for vehicle):

Although pain increases in all naloxone groups, the authors don’t expect that this is a result of naloxone increasing pain, but of natural history taking its course.

They infer a “placebo effect” from the observation that while the preprogrammed infusion pump injecting subjects with an inert substance increased their reports of pain greatly, an open injection of an inert substance decreased reported pain, and a hidden injection decreased it even more – a very strange placebo effect! Usually the difference between a hidden and open injection of an inert substance, with the open injection providing greater pain relief, is provided as evidence of a placebo effect. The authors conclude that

hidden infusion of vehicle may be accompanied by unintentional cues that elicit a placebo response, whereas machine infusion of vehicle does not provide such cues. Surprisingly, in post-experiment interviews, patients were unable to identify cues signalling when hidden infusions had occurred or what substance had been infused. Thus, subtle cues, of which a patient may not be consciously aware, can significantly influence therapeutic outcome.

Whereas I would conclude that it’s just noise in their 12-patient groups. But it’s lucky that they had the high-tech robot, otherwise it would be a negative result for placebo effects! Most of the studies rely on a hidden injection being undetectable, so to the extent that this study is to be believed, it casts doubt on many of the other results.

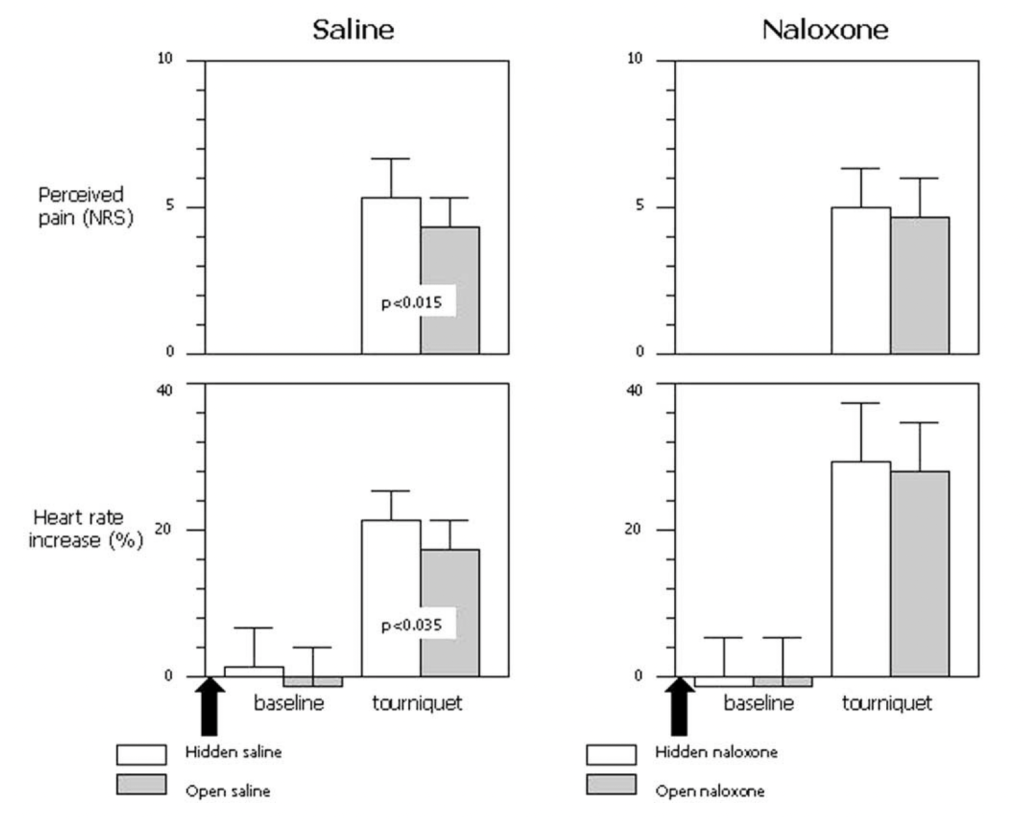

Now we have our last Benedetti paper, Pollo et al. 2003, Placebo analgesia and the heart. In the part of the study relevant to the meta-analysis, we are back to ischemic pain and tourniquets. They are using a pre-programmed infusion pump we just heard about for hidden injections. Each subject received either a hidden or an open injection. The groups relevant to us either got saline (hidden or open) or naloxone (hidden or open). Here are their results:

They find a small, significant placebo effect (the difference between hidden and open injections) in the saline group for both reported pain (p < .015) and heart rate (p < .035), but no significant difference (between hidden and open injections) for the naloxone group, although the naloxone group experienced a hilariously increased heart rate both before and after the pain trial. Although we know from Gelman and Stern (2006) that The difference between “significant” and “not significant” is not itself statistically significant, this insight came a few years late for this paper to benefit from it and perhaps offer further analysis. This is again using the method of inferring a placebo response from comparing hidden and open injections, rather than showing that naloxone reduces a previously-established placebo response.

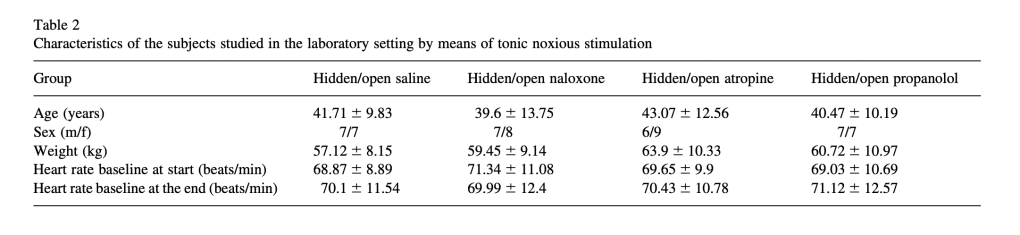

Second-to-last is Posner and Burke (1985), The effects of naloxone on opiate and placebo analgesia in healthy volunteers, another non-Benedetti study. They compare the effects of naloxone on subjects going through a tourniquet/hand squeezer paradigm. Subjects in different groups received a capsule containing either the opioid drug dipipanone, a lactose placebo, codeine, or no capsule. They also received an infusion of either naloxone or saline, administered by a pump but not hidden from the subject (although whether it contained saline or naloxone was hidden).

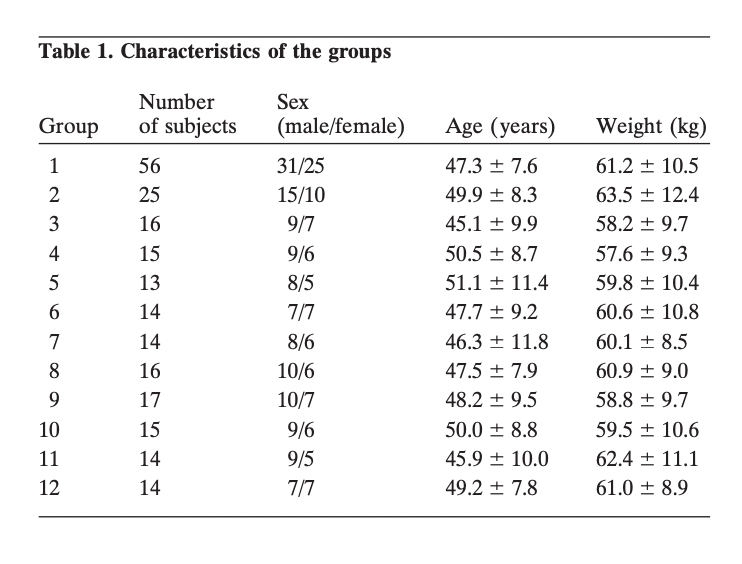

The authors measured both subjective pain ratings and total time the subjects could stand the tourniquet. While they found that naltrexone did reduce the effects of dipipanone in terms of both pain ratings and scores, there were no significant differences between the ratings or times of subjects who received placebo and naltrexone, on the one hand, or placebo and saline, on the other. They did induce a placebo effect, as both were better than “no treatment” at p < .05, but naltrexone did not affect it. Another non-Benedetti negative result. (The relevant groups are P/S, placebo/saline, and P/N, placebo/naloxone, the triangles below. B/B and B/N are no treatment with and without naloxone; C is codeine.)

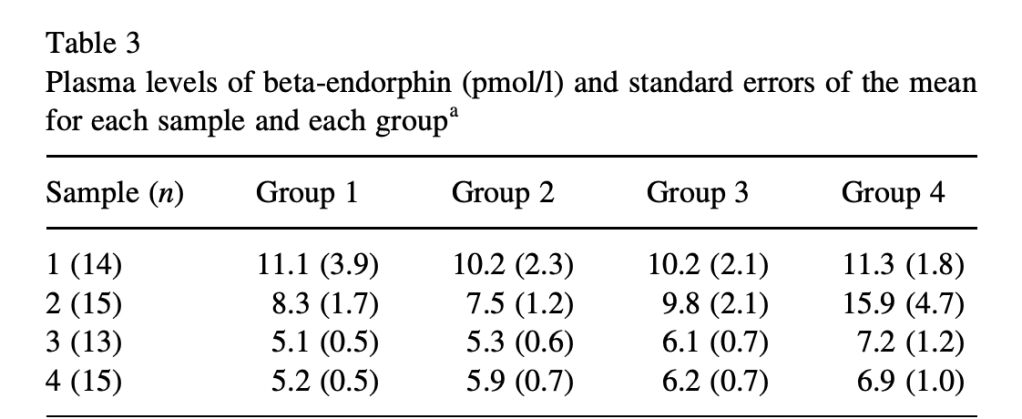

Finally, we have Roelofs et al. (2000), Expectations of analgesia do not affect spinal nociceptive R-III reflex activity: an experimental study into the mechanism of placebo-induced analgesia. As far as I can tell, this study is the only one to actually measure β-endorphins, which are supposed to be the whole point of this exercise. Sauro and Greenberg (2005) say that two studies did:

Two studies examined the effects of placebo administration on β-endorphin secretion. An effect size of 0.22 was calculated, but was insignificant (P = .36).

But after the review necessary to write this, I can’t figure out which other study they mean.

Roelofs et al. is the clearest and least confusing paper in the lot, specifying things that many papers leave up to the imagination (the procedure for randomization, the position subjects are to be seated in, how they store their data, etc.).

Roelofs et al. use electric shocks as their pain stimulus, with placebo groups (falsely) told they would receive fentanyl, and controls told they would receive either saline or naloxone. Each group completed three series of electric shocks and give pain ratings for each shock, one baseline, one after receiving saline (hyped as fentanyl or not), and one after a further injection if either naloxone or saline. They also measure β-endorphin levels from blood plasma samples taken four times, before and after each pain trial.

Surprisingly, despite (or because of?) their careful study design and practices, these authors don’t produce a significant placebo effect, reporting instead a very realistic -.5 points on a 100-point scale with a 95% CI of -5.8 to 4.8. β-endorphin levels were also not affected by the placebo billed as fentanyl, compared to honest placebo. And there was no effect of naloxone on the (nonexistent) placebo effect.

Study Arm Sizes

- Amanzio M, Benedetti F. Neuropharmacological dissection of placebo analgesia: Expectation-activated opioid systems versus conditioning-activated subsystems. J Neurosci 1999; 19:484 –494.

- Control groups of 56 and 25 that are not relevant to the naloxone reduction of placebo effect.

- Study arms of 13 to 17 subjects each, as shown:

2. Amanzio M, Pollo A, Maggi G, Benedetti F. Response variability to analgesics: A role for non-specific activation of endogenous opioids. Pain 2001; 90:205 –215.

- Relevant study arms of 13-15 subjects as shown:

3. Benedetti F. The opposite effects of the opiate antagonist naloxone and the cholecystokinin antagonist proglumide on placebo analgesia. Pain 1996; 64:535 –543.

- Control groups of either 60 or 10 subjects that were not relevant to the naloxone placebo reduction. Study arms of 15 subjects in relevant arms.

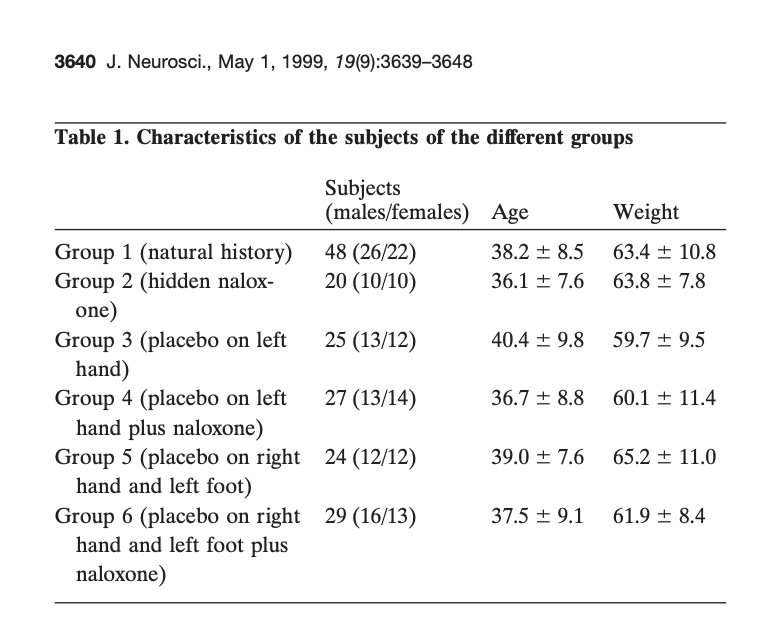

4. Benedetti F, Arduino C, Amanzio M. Somatotopic activation of opioid systems by target-directed expectations of analgesia. J Neurosci 1999; 19:3639–3648.

- Control groups of 48 and 20 not relevant to the comparison. Relevant study arms of 24-29 subjects:

5. Gracely RH, Dubner R, Wolskee PJ, Deeter WR. Placebo and naloxone can alter post-surgical pain by separate mechanisms. Nature 1983; 306:264 –265.

- 89 subjects across 6 groups. I can’t find the group allocation; let me know if you can.

6. Grevert P, Albert LH, Goldstein A. Partial antagonism of placebo analgesia by naloxone. Pain 1983; 16:129 –143.

- One group of 16 compared to one group of 14. The only group not including Levine or Benedetti to confirm the finding.

7. Hersh EV, Ochs H, Quinn P, MacAfee K, Cooper SA. Narcotic receptor blockade and its effects on the analgesic response to placebo and ibuprofen after oral surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1993; 75:539 –546.

- 11-16 subjects per relevant arm.

8. Levine JD, Gordon NC, Fields HL. The mechanism of placebo analgesia. Lancet 1978:654 –657.

- 17 and 23 subjects in the relevant comparison groups. Smaller subgroups are also analyzed.

9. Levine JD, Gordon NC. Influence of the method of drug administration on analgesic response. Nature 1984; 312:755 –756.

- 12 subjects in each relevant treatment group.

10. Pollo A, Vighetti S, Rainero I, Benedetti F. Placebo analgesia and the heart. Pain 2003; 102:125 –133.

- 14 or 15 subjects per relevant treatment group:

11. Posner J, Burke CA. The effects of naloxone on opiate and placebo analgesia in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacol 1985; 87:468 – 472.

- 12 subjects per study with a crossover design.

12. Roelofs J, ter Riet G, Peters ML, Kessels AGH, Ruelen JPH, Menheere PPCA. Expectations of analgesia do not affect nociceptive R-III reflex activity: An experimental study into the mechanism of placebo-induced analgesia. Pain

2000; 89:75 –80.

- 13-15 subjects per relevant group.

Placebos for Depression

An interesting rejoinder to the Hróbjartsson and Gøtzsche meta-analyses is that of Wampold et al. (2005), in The Placebo Is Powerful: Estimating Placebo Effects in Medicine and Psychotherapy From Randomized Clinical Trials. They reanalyzed the studies from the original meta-analyses but reclassified them according to their own criteria, including whether psychology graduate student raters identified the studies as amenable to placebo treatment, and whether they thought the study design attenuated the placebo effect. Their conclusion was that in the subgroup of studies that they found conducive to placebo effects, the placebo effect “is robust and approaches the treatment effect.” They are particularly sanguine for the treatment of depression with placebos.

They seem to be correct that for accepted therapies for depression, the placebo effect (placebo minus no treatment) is almost as large as the treatment effect (treatment minus placebo). But this doesn’t seem to be a point in favor of a powerful placebo, but rather against the efficacy of accepted therapies. For example, Fernández‐López et al. (2022) attempted to estimate the placebo effect in the treatment of various mental disorders, including depression. They meta-analyzed studies that compared some kind of placebo arm (a pill placebo, “pseudo-meditation,” “bogus training,” “non-directive counselling,” “advice about how to be more organized,” etc.) with a no-treatment arm (wait list, no treatment, treatment as usual, etc.). In their random effects model for depression only, the overall placebo effect was SMD = .22 (95% CI of .04 to .39). While these are small studies, half of which occurred before the year 2000 and only three out of ten of which used a pill placebo, the small effect size seems plausible to me as a measure of politeness or response bias. It is likely smaller for pill placebos, as the authors did not find a significant effect for the subgroup of pill placebos, but this also included other conditions like schizophrenia, not just depression (and I would note that this is because pill placebos to me imply higher study quality, not because they are less “effective”). An effect size of .22 for placebo in depression is likely an overestimate, but I can’t find a better one.

Compare this to well-studied treatments for depression. Cuijpers et al. (2014) meta-analyze psychotherapy (talk therapy) compared to pill placebo on depression. Five of the ten studies they analyze use cognitive-behavioral therapy, a mind-cure therapy widely regarded as evidence-based and scientific. They find an effect size of .25 (95% CI .14-.36), and translate this to a simple effect size of 2.66 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and 3.2 points on the Beck Depression Inventory compared to placebo. Furukawa et al’s 2017 meta-analysis of the five cognitive-behavioral therapy studies compared to pill placebo resulted in a SMD of .22 (95% CI .02-.42), identical to the placebo effect in the small meta-analysis above. As for the drugs, Stone et al. (2022) find an average drug-placebo difference of 1.75 points (95% confidence interval 1.63 to 1.86) on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in antidepressant trials submitted to the FDA.

Tangent: There are some other claims in the Stone et al. (2022) analysis that I will not get into detail about here, but one claim that has gotten a lot of attention is that Stone et al. find a latent distribution within the data that they label “Large,” having a 16-point mean improvement from baseline, and further find that 24.5% of drug-treated, vs only 9.6% of placebo-treated individuals fall within this latent distribution. This has been incorrectly interpreted as meaning that the drugs give a 15% greater chance for large improvement (e.g. Newsweek, “Antidepressants Work Better Than Sugar Pills Only 15 Percent of the Time“), but Stone et al.’s own supplementary figure shows that even this depressing mischaracterization is too optimistic:

Clearly, however things go for the unobservable-at-outset latent class that the authors identify, a class patients can’t know if they belong to when deciding on a treatment, the difference overall between drug and placebo at 16-points-or-greater appears to be much less than .15. End of tangent, back to the tiny effects of treatments for depression:

Turner et al. (2022) give a standardized effect size of .24 for newer antidepressants for trials submitted to the FDA and .29 for trials published in journals; for older antidepressants, the effect sizes are .31 for FDA trials and .41 for trials published in journals, possibly indicating a decreasing level of reporting bias. (Note that the drug studies represent 59 times as many patients as the talk therapy studies, so the fact that drug effects are well below the minimal clinically important difference of 3-6 points is probably more reliable than the clinically relevant difference for talk therapy on one self-report scale barely overlapping the clinically relevant difference of also 3-6 points, as estimated by Hengartner and Plöderl, 2022.)

In any case, the treatment effects are extremely modest, so modest as to not be noticeable by a typical patient or detectable by a typical clinician. While the certainty of evidence for the size of the placebo effect is very low, it is possible to conclude that, for conditions where treatment options are very poor, as meager as the placebo effect is, it might well approach the size of the treatment effect. This is hardly a point in favor of large placebo effects, even for self-reported criteria that can’t be distinguished from response bias. Patients in no-treatment groups in depression trials do very well, as it is an episodic disorder prone to regression to the mean, and patients in placebo groups do only slightly better.

Interestingly, although Hróbjartsson and Gøtzsche found a placebo effect for self-reported but not for observer-reported outcomes, in the case of antidepressant trials versus placebo, “placebo effects” seem to be larger when a researcher is doing the rating. In trials of depression treatments, both the placebo effect (Rief et al., 2009) and the treatment effect (Cuijpers et al., 2010) are larger for clinician-rated effects compared to self-reported effects. One interpretation of this is that the “placebo effect” in these trials is not so much from patients being polite and exaggerating their benefit, but from researchers exaggerating the change, either innocently or for the purpose of producing a larger apparent effect. Interestingly, a 2010 meta-analysis reported that this was also the case for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: higher placebo response rates for physician-reported than subject-reported outcomes. The negative result for outcomes measured by laboratory tests suggest this is exaggeration, rather than a genuine objective improvement.

One thought on “Appendix”

Comments are closed.