I describe two patterns here, one from the domain of the social, the other from the domain of the sacred. I discuss them together because they are of the same shape; the shape, or form, that they share is also shared with the human self.

Holy Ground

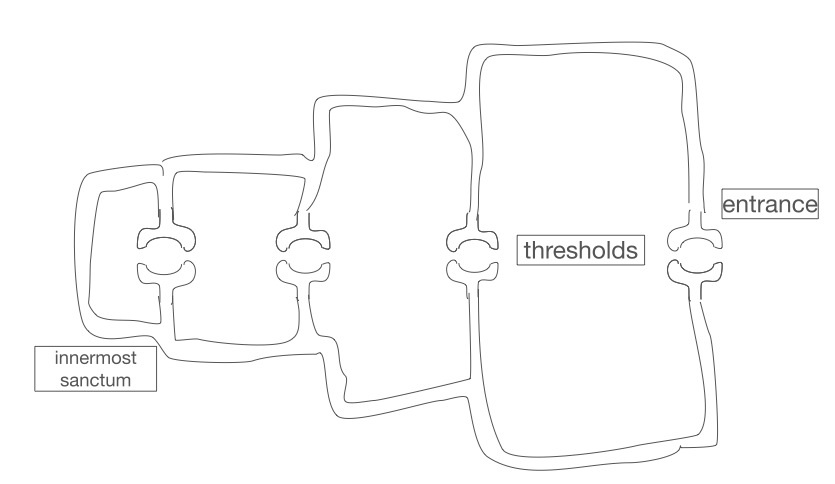

This is the visual form of the shape: [my drawing, adapting Christopher Alexander, A Pattern Language (1977), Pattern 66: Holy Ground (p. 334)]

The first pattern described by this shape is a common (perhaps invariant) form across many cultures for encountering the sacred. Alexander’s Holy Ground, above, calls for the preservation of the sanctity of Sacred Sites (Pattern 24) with a specific architecture: “a series of nested precincts, each marked by a gateway, each one progressively more private, and more sacred than the last, the innermost a final sanctum that can only be reached by passing through all of the outer ones.”

This pattern is also seen, to similar effect, in Beijing’s Forbidden City, with its awesome and exhausting approach of nested gates, gardens, and halls, a “magic show” that concealed within a rather mundane group of human beings.

The sacred is approached only through successive boundaries of porous exclusivity. This experience may be necessary to facilitate the experience of the sacred. “The organization is so powerful,” Alexander says hopefully, “that to some extent it can itself create the sacredness of sites, perhaps even encourage the slow emergence of coherent rites of passage” (Pattern 66). The pattern at least makes it possible for rituals to emerge.

Intimacy Gradient

The second pattern, united with the first pattern in its shape, is a pattern in human social organization. It is that people need to be provided with many degrees of public and private, a gradient of intimacy occupied by progressively intimate groups. The binary of public and private is not enough; just as we must have progressively intimate realms to approach the sacred, we need progressively intimate realms to express our social selves. Porous exclusivity characterizes each layer of the structure.

This meta-pattern finds form in many specific architectural patterns. Pattern 13 Subculture Boundary and Pattern 15 Neighborhood Boundary define realms of intimacy at the neighborhood level. 98 Circulation Realms describes a cognitive reason we might want building complexes in this shape: they are easy for the mind to grasp, and easy to give directions within them. 158 Open Stairs, 112 Entrance Transition, and 88 Street Cafe provide connection, as well as comfortable porous exclusivity, between the street realm and indoor realms. 36 Degrees of Publicness, 111 Half-Hidden Garden, and 127 Intimacy Gradient illustrate this pattern within and around residences, down to the room level. These layers of porous boundaries allow overlapping social groups of progressive intimacy to flourish; it is the architecture of comfortable peopling.

In low-trust societies that are not functioning well, these layers of porous boundaries must be barred and locked. People are left with a binary choice between a vulnerable “public” that is exposed to all, and a socially dead “private” that is disconnected from others (whether inside a home or vehicle). Unfortunately, the internet has mirrored the trajectory of the society at large. Beginning as a set of overlapping zones (and communities) with distinct character and porous exclusivity, it increasingly resembles the binary public/private of our built environment. Search algorithms and unlimited computing resources mean that every communication that is not explicitly private is functionally public, in the most global way that has ever been possible. Facebook and Google+ have features that rationally appear to be circles of progressive intimacy; the audience for a given communication may be limited to one’s friends, family, or other circle or group. Theoretically, this might support groups of porous exclusivity, but I think the choice to collapse each person’s identity into a single “character” (e.g. Google’s erstwhile “real names” policy) is enough to destroy the pattern. In all social media, the service provider finds many ways to encourage users to add new acquaintances – new watchers, to be ominous – gradually making communications increasingly public.

These virtual boundaries are maintained by inscrutable corporations, are constantly changing, and cannot be relied upon. They tend to move in the direction of extreme publicness. Twitter, for years an unexpected jewel of social interaction, has moved toward making its distinct functions – the retweet and the favorite – more like each other, in the direction of the more public retweet. Making one’s account private and speaking via direct messages put one behind a non-porous boundary; the only other option is speaking publicly, and it is increasingly public indeed. It is not the semi-private, high-trust place for the development of ideas that it once was.

Are sacred experiences possible on the internet? Even if the pattern of nested precincts with thresholds is realized (as it is, for instance, in many video games, to great effect), there is still the matter of a source of sacredness to approach. Mostly on the internet we read, talk to people, listen to music, watch videos, or play games – interacting exclusively with other people and their creations. These activities are not common in sacred spaces, in which something transcending the merely human is sought. But in many of our minds, perhaps, suggestions of mystical power still attach to the old-fashioned notion of Cyberspace. Perhaps enough minds secretly expect an inhuman, nascent intelligence to look back at us (though preferably not quite slouching toward Bethlehem to be born). To experience the sacred requires mystery.

The Self

The pattern so far described is also reflected in the human self — the human self being literally the reflection of one’s social spheres. According to Philippe Rochat, we are “constrained toward (self-)consciousness” by other people in our environment (Others In Mind: Social Origins of Self-Consciousness, 2009). We must keep others in mind, model their cognition and emotion, in order to monitor our reputation and simulate future scenarios involving them. We see ourselves through the eyes of others, adding a third-person perspective to our first-person experience. And the self, properly located, exists not deep within us, but in between ourselves and others.

The social context – the role we are in, the others we are interacting with and exposed to – determines the information, memories, and behaviors our minds have access to. This is revealed in word-completion tasks, but may sometimes be detected through introspection. We are different selves with different minds depending on the audience. If there is a unified authentic self, it exists between and among these many context-adapted selves, in the transformation from self to self, rather than in any one of them. To collapse the many selves into one is not to realize authenticity, but to destroy oneself.

With selves, as with the architecture they exist in, the binary choice between public and private is not adequate. A completely public self is a play-acted character; more intimate selves, performed for closer circles, are more crucial to the project of peopling. More public selves, while more “porous” and open to making new connections, are also more vulnerable to criticism and other negative information about themselves. Negative information about the self causes painful shame (even seeing oneself in the mirror for the first time – see Rochat, pp. 30-31), forcing one out of the idealized first-person perspective of the self and toward a much harsher third-person view of the self. It is no exaggeration to say that the present generation experiences more of this socially-reflected negative information about the self than any generation that has previously lived on earth. Roy Baumeister has argued that the shameful weight of the modern self — unprecedented pain of self-awareness — drives us to try to escape ourselves though hobbies like alcoholism, suicide, sadomasochistic sex, evangelical religion, and binge eating.

Can any guidance be found from deep within the self, as is our modern expectation? Unfortunately, the innermost sanctum, in this case, is quite empty. Christopher Knight, the man who lived without human contact in the Maine woods for 27 years, agreed with Rochat that the experience of the self seems to exist only in relation to others:

“I did examine myself,” [Knight] said. “Solitude did increase my perception. But here’s the tricky thing—when I applied my increased perception to myself, I lost my identity. With no audience, no one to perform for, I was just there. There was no need to define myself; I became irrelevant. The moon was the minute hand, the seasons the hour hand. I didn’t even have a name. I never felt lonely. To put it romantically: I was completely free.”

Most of us could not stand austere, complete freedom like this. We require social interaction, and to accomplish this, we need social forms that can connect us together without collapsing us individually. The world inside the mind reflects the world outside the mind. We can’t have ancestral lives (nor would we necessarily want them), but if we can incorporate ancestral patterns into our strange new lives through ostension, these patterns may help us coordinate with each other as well as manage the weight of our own consciousness.

For intimacy gradients in social groups see also Robin Dunbar’s new book on evolution, just called Human Evolution, published by Pelican. Each average person surrounded by concentric layers of groups membership with decreasing intimacy. Sacred sites seem to recapitulate that kind of pattern.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! Scaling up to global megacomplexity while leaving Dunbar-number groups intact is proving to be a huge problem.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You may like my recent post on nesting.

http://leavingbabylon.wordpress.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

Academia looks like an example of the holy ground structure – undergraduate, grad student, assistant professor, tenure, emeritus. Each tier is smaller, and (usually) you have to go through them in order. My impression is that those near the top also tend to view academia as a sacred thing. Perhaps there’s something causal going on.

Really, any hierarchy seems to have roughly have this structure, but only some have the sacredness attached to it. Think about corporate management and the varying levels of respect given to the top in different companies. The sociopaths (in the http://www.ribbonfarm.com sense) take advantage of this structure, but I don’t think they put it there. It seems to be a feature of humanity. Perhaps successful hierarchies are successful partially because the holy ground structure gets the low and mid level members to buy in instead of defecting to greener pastures and prevents the top level members from abusing their position too much.

Cetarus paribus of course. If the hierarchy strongly selects for people willing to profane the sacred, there will be problems. Caesar will cross the Rubicon. Everyone else will cut smaller corners to get their way. I’m not sure if this fits into the holy ground metaphor – maybe it’s punching holes through walls to find other paths to the inner sanctum, thereby decreasing the holiness and increasing the chance that someone else will follow or knock their own hole in the wall, though “the top cutting corners” doesn’t seem to fit into this.

/spitiballin’

LikeLiked by 1 person

Academia is modelled on much older ecclesiastical hierarchies. That’s also why the top guys are “professors”. Like a confessor but in reverse. One can fess up and also fess down. The first universities were more or less monasteries for training religious teachers. The American Structure you cite is a modification of the European system. In English the structure is lecturer (one who stands at the lectern); senior lecturer; reader (= assoc. prof); and professor. The university is run by a chancellor – the one in the chancel or inner sanctum of a chapel – who is about equivalent to a bishop (who has a seat in the chancel). In some places the graduation ceremony is still partly in Latin, the language of the Roman Church. In academia one advances by degrees.

There’s an interesting parallel between the lowest academic award of “bachelor” (literally an unmarried man) and the Sanskrit term “brahmacārin” which means “a follower of God” but indicates a young unmarried male student who lives with their religious teacher.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had an interesting thought that you probably can unpack better than I can: layers of increasing sacredness leading to an inner sanctum can present either bare, spartan exteriors and ornate, splendid interiors, or the other way around. In the first kind, each layer looks bare on the outside, but once you get in and look behind you at the inner walls, they are dazzling. Malls are an example, with all the dazzle on the inside walls. These tend to be very private cultures, like American shopping culture. On the the other hand, if the outer walls are showy and the inner ones bare, the culture tends to be performance oriented. I think the same holds for people. There are people who are boring on the outside, interesting once they open up to you and you get to know them. And there are people who are interesting on the outside, but get boring once you know them. For many layered people, as you get through deeper layers, you go through a cycle of either overpromise/underdeliver or underpromise/overdeliver as you are allowed into each layer.

Perhaps it’s a bias, but I think the dazzling outside/bare inside shell structure is fundamentally weaker. It advertises itself and tries draw more people in. The other kind must be accessed through work. You earn the privilege of inner views. Something like that. The Vatican is showy both on the inside and outside. Indian temples tend to be showy on the outside, bare on the inside. Indian homes on the other hand, tend to be bare on the outside, showy on the inside, the exact opposite of American homes. This is reflected in the religions: Christianity is very strong institutionally, but weak in homes. Hinduism is the opposite. Shopping culture is the same way. American malls represent a very powerful shopping culture, while open, communal bazaar type architectures tend to represent a weak shopping culture today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d like to see how this changes over time in different groups in different places. American shopping culture seems to grow more powerful as other forms of public space lose their draw.

This reminds me of Nick Szabo’s ultimate example of plain-on-the-outside – the Dutch townhouses in Amsterdam, taxed based on frontage, that were built extremely long to maximize space while avoiding taxes – http://nakamotoinstitute.org/measuring-value/. The interface presented to the outside world varies a great deal with (often non-obvious) incentives. The patterns in the “fanciness” dimension can perhaps reveal some of the hidden incentives (and tastes) of the people making things fancy in that particular way.

One of my friends visiting the US for the first time described the public space in the urban US as “either a fortress or a ruin.”

I spent a cumulative total of several hours, over the course of years, staring at an ornately-carved wooden temple gate in the Norton Simon museum in Pasadena without being able to see the most important thing about it, because it was presented on a wall like a painting: it’s a gate. It clearly wasn’t meant to have a serious security function – its function was delineation of space (beautifully elaborated with figures).

Totally unrelated: this is another brilliant guy whose bunny hole you should totally check out http://countercomplex.blogspot.com

LikeLike